采用计算方法的组合式蛋白质设计策略

丁香园

3176

1. 介绍

1.1 蛋白质设计

通过对蛋白质结构(包括那些具有特殊功能结构)的设计,研究者可以増进对决定蛋白质折叠状态特征的力和效应的理解。另外,对特定折叠结构设计的控制,可能得到新的具有生物效能和特异性的合成蛋白。这样的应用包括在医药、传感器、催化剂和材料等领域。甚至在尚未完全和定量地理解决定蛋白质结构的力的条件下,蛋白质设计仍有可能取得成功。

但是,由于决定蛋白质折叠态的相互作用的复杂性和精细性,蛋白质设计不是一件轻而易举的事。蛋白质是巨大的分子(含数十到数百个氨基酸残基),折叠态的给定需要许多的结构变量,其中包括序列、主链拓扑和侧链构象。即使主链结构已经给定,每个残基仍可能有多重构象。除了结构的复杂性之外,还有序列的复杂性。设计意味着从无数的可能的序列中,鉴别出可折叠的序列。在折叠蛋白中观察到的高度“一致性” 引导这个搜索过程 [1] 。一般来说,处于折叠状态的蛋白质,在原子水平上,通过有利的范德华相互作用、疏水残基与溶剂隔离,并使大多数氢键作用都被满足而恰当地堆积。但这种一致性通常都是复杂的,可能没有什么能使问题简化的对称性。另外,精确地定量非共价相互作用属于最困难的一类问题,并且,估计残基替换或结构有序化的自由能,仍然是计算研究中最深奥的领域 [ 2,3 ] 。与预测能力相反,目前,我们还不能期望用详细的模拟估计自由能变化的方法,来确定大量序列的相对稳定性变化。尽管如此,从小分子和蛋白质数据库导出的分子位能,确实包含了已知的,对决定蛋白质结构起重要作用的,相互作用和力的部分信息。在某些情况下,这些位能的优化,已经在蛋白质设计中获得显著的成功 [ 4 ] 。这样的位能肯定是近似的,并且这样设计的任何序列,很可能对特定的位能和采用的目标结构敏感。作为另一种选择,在这些位能中包含的部分信息也可以做概率性的应用,以得到出现某种氨基酸的可能性。概率性方法也适合于确定可折叠到同一结构序列的完整可变性,因为似乎存在大量这样的序列—— 远大于可以用序列搜索或列举方式所能处理的。

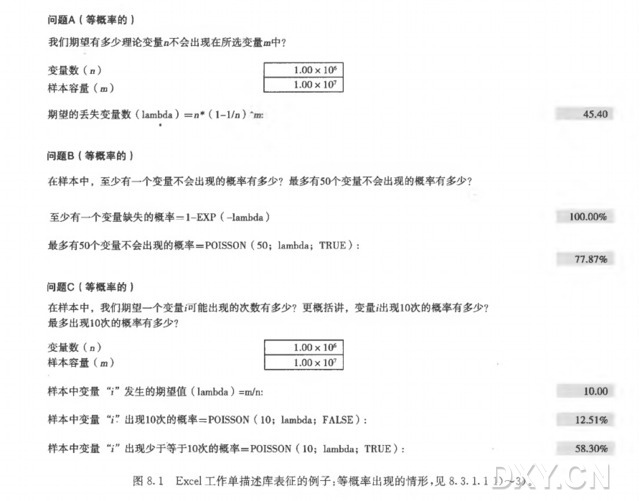

这样的概率性方法也特别适合于在蛋白质组合实验中的全新设计,这些实验能产生并快速测试许多序列。虽然组合方法能处理大量序列(104~1012 ) ,但这些数量与可 能的蛋白质序列数比较仍然是无穷小,如对 100 个残基的蛋白质,这个数是 20100≈10130 ( 为了对 10130 这个数有多大有个一般的了解,假定合成出一条 100 个残基的蛋白质序列约需要 10000 /N g 物质,N≈6 X 1023,是阿伏伽德罗常数,那么合成出 10130 条序列需要超过 10107 kg 的物质。这个数量远超过目前我们所知宇宙物质的总质量 1035 kg一一译者注)。于是,即使是采用组合法,我们仍然必须集中于序列空间选定的一小部分。通过预先观察,在蛋白质中选定若干残基位点并在这些选定的位点允许残基的全部或部分可变性(全部可变性,即可以替换为 20 种氨基酸中任何残基;部分可变性, 只替换为某些类型的残基—— 译者注)来实现对序列空间的限定。近来发展了可以在宽得多的范围内追踪序列可变性,并提供扫视和聚焦序列空间的定量计算方法。在这里, 我们讨论序列设计的计算方法,把重点放在处理给定结构位点特异氨基酸可变性的概率方法。

1.2 蛋白质设计的定向方法

这里的 “定向蛋白质设计”是指鉴定出一条(或一组)可能折叠为预先指定的主链结构的序列。然后可以用多肽合成或基因表达的办法,实验性地实现每一条这样的序列,以确认其折叠态及其他分干性质。早期的设计努力,是在已观察到的自然发生的结构和已被确认的蛋白质序列的指导下完成的,它们有着重要的二级结构,但并不必 有明确的三级结构 [ 5 ] 。由于能够定量化并以表格列出残基间相互作用,计算方法已经极大地加速了蛋白质设计的成功率。典型情况下,这样的方法使序列搜索成为优化过程,在过程中改变氨基酸身份和侧链构象,以优化定量化序列结构相容性的打分函数, 对所有 mN 个可能序列的完全搜索,只有仅仅少量的残基 N 是允许改变的,或允许改变的氨基酸数目显著地减少,如从 m=20 减少到 m=2 时才是可行的。为了达到从内部平均来看有利的原子间相互作用的合理堆积序列,必须搜索每个氨基酸的不同侧链构象(旋转异构态)(见参考文献 [6])。结果,因为一个残基所可能有的状态数 m 增加 10 倍或更多—— 这取决于每个残基的旋转异构态数目和增加搜索的复杂性。如果只有很少的残基被允许改变,并且剩下的残基的构象受到限制,就可以对所有可能的组合完成完整数值计算,以鉴别出低能量的序列旋转异构态组合。由于(这个组合数)对链长和旋转异构态数目的指数依赖性,这样的完整数值计算在典型的情况下不能实现。在这样的情况下,序列空间可以用定向的方式取样以逐渐朝优化的(或部分优化的)序列方向移动。随机方法,如遗传算法和模拟退火,包含对序列空间的部分随机式搜索。在这种搜索中,搜索逐渐地移向髙分(低能)序列 [ 7~10 ] 。这样的搜索有足够的“噪声” 或重组,以允许越过序列-旋转异构地形图的局部极小值。当运用于精细到原子的表象中时,随机方法基本上集中于用疏水残基重新堆积结构的内部 [9] ,并已被用于 434 Cro、G 蛋白的 B1 结构域、WW 结构域和螺旋束的野生型结构。虽然在许多情况下这些方法对鉴别出实验可行的序列 [4,15 ] 有帮助,但是随机搜索法不必鉴别出整体优化点 [16] 。对只含有位点和对相互作用的位能,通过排除法,如 “死点排除法”,能找到整体优化点 [ 16~20 ]。这样的方法可连续地移除不可能是整体优化点的氨基酸-旋转异构态,直到再没有态可被移除。Mayo 研究组应用这一方法,已使拟 28 残基锌指蛋白 [21] 和在疏水和极性位点模式化之后的 51 残基同源域蛋白模体 [22] 的完整序列设计自动化。该组还重新设计了数种蛋白质内的部分残基组 [ 23~25 ] 。其功能性质,如结合金属或催化,也可以包括作为设计过程的元素 [ 26~28] 。蛋白质定向设计的要素和算法是最近一些综述的主体 [4,29,30 ] 。

尽管取得了某些惊人的成功,但序列定向设计的计算方法在鉴别折叠为特定结构的蛋白质序列特征上仍有局限性。随机方法可用于大蛋白,也容许多位点上的同时变化,但是,即使用于小蛋白,这样的计算消耗的机时和资源也是巨大的。定向方法对于使用的能量或打分函数必定是敏感的,因为它能鉴定能量函数的优化点。但是,所有这样的函数也必定是近似的,并且能量函数中的不确定因素可能不允许对整体优化点的搜索。许多天然存在的蛋白质是没有优化的。实际上,多数蛋白质只有微小的折叠稳定性,如 △G° < 10 kcal/mol [31] 。更有甚者,在功能上与其他分子结合的序列在结构稳定性上不必是整体优化的。重要的是发展与定向蛋白设计互补的方法,这些方法揭示可能折叠为某特定结构但又可能在结构上有未被优化的序列的特征。这样的技术可用于设计蛋白质序列。另外,这样的计算方法还可用于新型的蛋白质设计研究——组合式实验,即实验中大量蛋白质可以同时合成和筛选。

1.3 蛋白质设计的概率性方法

在蛋白质涉及的范围内,我们用定点氨基酸概率而不是特定的序列来描述“概率性蛋白质设计”。相对于定向的或决定论方法,概率性方法是常用于对问题只有部分信息场合的定量科学。对蛋白质设计,折叠过程的复杂性和不确定性促成了这样的概率性方法。蛋白质折叠是一个复杂的动态过程,有无数的相互作用规定折叠状态。每一个导致稳定的非共价键相互作用在大小上都是可以相互比较的,似乎没有哪一个具有压倒优势,以致于在折叠中起决定作用。定量化这些相互作用的办法,必定是近似的(见注 1 )。概率性设计方法也直接提供非常有用的序列信息,特别是在结构上重要的氨基酸。氨基酸概率可以引导特定序列的设计,也能够凸显能容忍突变、对结构只有微小影响的位点;在几轮蛋白质设计之后,这样的位点可以成为用来改变的目标。

概率性方法可以以几种方式应用于蛋白质设计。序列应该以符合计算出的概率方式生成。首先,最直接的选择是一个共用序列,或在每一个位点用最可能的氨基酸组成的序列。在必要时,可以重复地计算,逐次地增加蛋白质中(已经确定的)的残基。用这样的方法,已得到 114 个残基的双核金属蛋白 [32] 和一个完整膜蛋白的可溶性变体 [33] 。其次,计算概率可用于引导对序列的搜索,已提出基于 Monte Carlo 的方法。在 Monte Carlo 轨道的每一点决定序列的接受或拒绝时,计算的氨基酸概率用作有倾向性的选择标准 [ 34 ] 。用这样的方法处理相关的氨基酸身份,但要付出用于搜索的计算运转开销, 如果有信息可用于搜索,开销可以减少。最后,概率性方法可以用来定量地指导蛋白质组合库的设计 [ 35 ]。

1.4 组合实验

组合的蛋白质实验可以用来研究序列结构相容性和发现折叠为特定结构的新序列。在蛋白质组合设计实验中,筛选大量的序列(实物库),以找到以折叠为预先确定结构的迹象。取决于序列的离散性是如何产生和检验的,这类实验可以探测大量序列序列数可高达 1012 [36] 。可以用选择性分析,如配体结合或催化活性筛选序列(实物)库。以序列离散程度受研究者控制的方式,这样的实验可以“超越蛋白质序列数据库”。由于去掉了与天然蛋白进化压力的耦合,可以研究对折叠(和其他生物学性质)重要的特征。组合方法已用于鉴别螺旋蛋白 [ 37~39 ] 、泛素变体 [40]、单层自组装蛋白 [41]、具有纤维样性质的蛋白 [42] 以及稳定的寡聚螺旋 [ 43 ]。最近发表了几篇出色的关于组合实验和方法的综述 [44~47]。

1.3 注

1. 自洽的方法对整体优化不是最好的 [16] 。对蛋白质设计,这通常是因为在类平均场理论中处理残基身份和构象态之间相关的近似方式,随机取样和排除法常提供较好的结果。

2. 在设计序列时,主链柔性必须考虑。在天然蛋白质中,主链的微小调整会导致突变 [ 70,71 ]。但是,大多数计算方法把主链处理为刚性的,因为包括进柔性要消耗大量计算资源。统计理论的概率特性提示其预测剖面对主链选择较不敏感。当能量(或有效温度),在热容量 Cv 的峰值 [59] 之上,从蛋白 L 的 21 个稍有差别的主链结构得到的氨基酸剖面都相似。对微小的结构涨落均方差为 1A 紧密相关的序列特性会出现在 Ec 值达到或高于这个热容量峰值时。

3. 在完成熵受限制的优化时,我们发现利用这些方程的寻根法与限制性极小化算法表现得同样好。

4. 氨基酸的计算概率也可以用来计算对突变的容忍度。这样的突变在体外的定向蛋白进化实验 [72] 中在具有宽泛的氨基酸分布位点(在这些位点上许多氨基酸具有与最可能的氨基酸可比较的概率)最容易积累。

参考文献

1. Go, N. ( 1 98 3 ) Theoretical studies of protein folding. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1 2, 183-210.

2. Shea, J. E. and Brooks, C. L. 3rd. (200 1 ) From folding theories to folding proteins: a review and assessment ofsimulation studies of protein folding and unfolding. Anrvu. Rev, Phys. Chem. 5 2, 499-535.

3. Brooks, C. L. 3rd. (2002) Protein and peptide folding explored with molecular simulations. Acc. C/iem. 35,447-454.

4. Kraemer-Pecore, C. M. , Wollacott, A. M. , and Desjarlais, J. R. ( 2 0 0 1 ) Computational protein design.Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 5 , 690-695.

5. Bryson, J. W. , Betz, S. F. , Lu, H. S. , et al. ( 1 99 5 ) Protein design: a hierarchic approach. Sczenc^ 270,935-941.

6. Dunbrack, R. (2002) Rotamer libraries. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1 2, 431-440.

7. Shakhnovich, E. I. and Gutin, A. M. ( 1 99 3 ) A new approach to the design of stable proteins. Protein Eng. 6 ,793- 800.

8. Jones, D. T. ( 1 99 4 ) De novo protein design using pairwise potentials and a genetic algorithm. Protein Sci. 3,567-574.

9. Hellinga, H. W. and Richards, F. M. ( 1 99 4 ) Optimal sequence selection in proteins of known structure by simu-lated evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9 1 , 5803-5807.

10. Desjarlais, J. R. and Handel, T. M. (1 99 5 ) De novo design of the hydrophobic cores of proteins. Protein Sci. 4 ,2006-2018.

11. Johnson, E. C. , Lazar, G. A. , Desjarlais, J. R. , and Handel, T. M. ( 1 999) Solution structure and dynam-ics of a designed hydrophobic core variant of ubiquitin. Struct. Fold. Des.7, 967-976.

12. Jiang, X ., Farid, H. , Pistor, E. , and Farid? R. S. (2000) A new approach to the design of uniquely foldedthermally stable proteins. Protein Sci.9, 403-416.

13. Jiang, X. , Bishop, R J. , and Farid, R S. ( 1 997) A 办 wcrlo designed protein with properties that characterize natu_ral hyperthermophilic proteins. /. Am. Chem. Soc. 11 9, 838, 839.

14. Bryson, J. W. , Desjarlais, J. R. , Handel, T. M. and DeGrado, W. F. ( 1 998) From coiled coils to smallglobular proteins: design of a native-like three-helix bundle. Protein S ci. 7 , 14 04-1414 .

15. Walsh, S. T. R. , Cheng, H. , Bryson, J. W. , Roder, H. , and DeGrado, W. F. ( 1 999) Solution structure anddynamics of a de novo designed three-helix bundle protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9 6, 5486-5491.

16. Voigt, C. A. , Gordon, D. B. , and Mayo, S- L. (2000) Trading accuracy for speed: a quantitative comparison ofsearch algorithms in protein sequence design. J . Mol. Biol.299, 789-803.

17. Gordon, D. R and Mayo, S L. (1998) Radical performance enhancements for combinatorial optimization algorithms basedon the dead-end elimination theorem. /. Comput. Cherru 19, 1505-1514.

18. Gordon, D. B. and Mayo, S. L. (1 999) Branch-and terminate: a combinatorial optimization algorithm for proteindesign. Struct, Fold. Des. 7, 1089-1098.

19. Pierce, N. A. , Spriet, J. A. , Desmet, J. , and Mayo, S. L. (2000) Conformational splitting: a more powerfulcriterion for dead-end elimination. /. Comput. Chem. 2 1 , 999-1009.

20. Looger, L. L. and Hellinga, H. W. (200 1 ) Generalized dead-end elimination algorithms make large-scale proteinside-chain structure prediction tractable: implications for protein design and structural genomics. J . Mol. Biol. 307,429-445.

21. Dahiyat, B. I. and Mayo, S. L. ( 1 997) De novo protein design: fully automated sequence selection. Science 278,82-87.

22. Marshall, S. A. and Mayo, S. L. (200 1 ) Achieving stability and conformational specificity in designed proteins viabinary patterning. J . Mol. Biol. 30 5 , 619-631.

23. Malakauskas, S. M. and Mayo, S. L. ( 1 998) Design, structure, and stability of a hyperthermophilic protein vari-ant. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5 , 470-475.

24. Strop, P. and Mayo, S. L. ( 1 999) Rubredoxin variant folds without iron. J . Am. Chem. Soc. 1 2 1 , 2 341-2 345 .

25. Shimaoka, M. , Shifman, J. M. , Jing, H. , Takagi, L. , Mayo, S. L. , and Springer, T. A. (2000) Computa-tional design of an integrin i domain stabilized in the open high affinity conformation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7,674-678.

26. Benson, D. E. , Wisz, M. S. 9 Liu, W. , and Hellinga, H. W. ( 1 998) Construction of a novel redox protein byrational design: conversion of a disulfide bridge into a mononuclear iron-sulfur center. Biochemistry 37,7070-7076.

27. DeGrado, W. F .,Summa,C. M . , Pavone,V . ,Nastri,F . , and Lombardi,A. (1 999) De novo design andstructural characterization of proteins and metalloproteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 6 8, 779-819.

28. Bolon, D. N. and Mayo, S. L. (200 1 ) Enzyme-like proteins by computational design. Proc. NatL Acad. Sci. USA98, 14 27 4 - 14 279.

29. Street, A. G. and Mayo, S. L. (1 999) Computational protein design. Struct. Fold. Des.7, R 105-R 109.

30. Saven, J. G. (200 1 ) Designing protein energy landscapes. Chem. Rev. 1 0 1 , 3113-3130.

31. Gromiha, M. M. , Uedaira, H. , An, J. , Selvaraj, S. ? Prabakaran, P. , andSarai, A. (2002) Protherm, ther-modynamic database for proteins and mutants: developments in version 3. 0. Nucleic Acids Res. 3 0, 301> 302.

32. Calhoun, J. R. , Kono, H. , Lahr, S. , Wang, W. , DeGrado, W. F. , and Saven, J. G. (200 3 ) Computationaldesign and characterization of a monomeric helical dinuclear metalloprotein. J . Mol. Biol. 334, 11 0 1 - 1115 .

33. Slovic, A. M. , Kono, H. , Lear, J. D. , Saven, J. G. , and DeGrado, W. F. (200 4) Computational design of wa-ter-soluble analogues of the potassium channel kcsa. Proc, Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1 0 1 , 1828-1 833.

34. Zou, J. and Saven, J. G. (200 3) Using self-consistent fields to bias monte carlo methods with applications to desig-ning and sampling protein sequences. J. Chem, Phys. 1 1 8 , 3843-3854.

35. Park, S. , Kono, H. , Wang, W. , Boder, E. T. , and Saven, J. G. (200 5) Progress in the development and ap-plication of computational methods for probabilistic protein design. Comp. Chem, Eng. 2 4 , 407-421.

36. Keefe, A. D. and Szostak, J. W. (2 0 0 1 ) Functional proteins from a randomsequence library. Nature 41 0,715-7 1 8.

37. Rojas, N. R. L. , Kamtekar, S. , Simons, C. T. , et al. .(1 997) Denovo heme proteins from designed combinato-rial libraries. Protein Sci. 6 , 2 512-2524.

38. Roy, S. , Ratnaswamy, G. , Boice, J. A. , Fairman, R. , McLendon, G. , and Hecht, M. H. (1 997) A proteindesigned by binary patterning of polar and nonpolar amino acids displays native-like properties.J.A m . Chem, Soc. 11 9 , 5302-5306.

39. Roy, S. , Helmer, K. J. , and Hecht, M. H. (1 997) Detecting native-like properties in combinatorial libraries ofde novo proteins. Fold. Des. 2, 89-92.

40. Finucane, M. D. , Tuna, M. , Lees, J. H. , and Woolfson, D. N. ( 1 999) Core-directed protein design. I. An ex-perimental method for selecting stable proteins from combinatorial libraries. Biochemistry 3 8, 11 > 6 0 4 , 1 1 ,612.

41. Xu, G. F. , Wang, W. X. , Groves, J. T. , and Hecht, M. H. (200 1 ) Self-assembled monolayers from a designedcombinatorial library of denovo beta-sheet proteins. Proc. Natl, Acad. Sci, USA 98, 3652-3657.

42. Case, M. A. and McLendon, G. L. (2000) A virtual library approach to investigate protein folding and internalpacking. J . Am. Chem. Soc. 1 2 2, 8089, 8090.

43. Arndt, K. M. , Pelletier, J. N. , Muller, K. M. , Alber, T. , Michnick, S. W. , and Pliickthun, A. (2000) Aheterodimeric coiled-coil peptide pair selected in vivo from a designed library-versus-library ensemble./. Mol. Biol.29 5 , 627-639.

44. Zhao, H. M. and Arnold, F. H. ( 1 997) Combinatorial protein design: strategies for screening proteinlibraries. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 480— 485.

45. Giver, L. and Arnold, F. H. ( 1 9 9 8 ) Combinatorial protein design by in vitro recombination. Curr. Opin.Chem. Biol.2, 335-338.

46. Hoess, R. H. (200 1 ) Protein design and phage display. Chem.Rev. 1 0 1 > 3205-3218.

47. Moffet, D. A. and Hecht, M. H. ( 2 0 0 1 ) De novo proteins from combinatorial libraries. C/iem. 1 0 1 ,3191-3 203 .

48. Holm, L. and Sander, C. (1 998) Touring protein fold space with dali/fssp. Nucleic Acids Res. 2 6 , 316-319.

49. Luthy, R. , Bowie, J. U. , and Eisenberg, D. ( 1 992) Assessment of protein models with 3-dimensional pro-files. Nature 356, 83-85.

50. Durbin, R. , Eddy, S. , Krogh, A. , and Mitchison, G. ( 1 998) Biological Sequence Analysis ?. ProbabilisticModels o f Proteins and Nucleic Acids,Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

51. Raha, K. , Wollacott, A. M. , Italia, M. J. , and Desjarlais, J. R. (2000) Prediction of amino acid sequence fromstructure. Protein S ci. 9 9 11 0 6 - 111 9.

52. Kuhlman, B. and Baker, D. (2 0 0 0 ) Native protein sequences are close to optimal for their structures.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, USA 97, 10383-10388.

53. Koehl,P.L .M . (1 9 9 9 ) De novo protein design. I. In search of stability and specificity. J . MoZ. BzoZ. 2 3 9,1161 - 11 8 1 .

54. Koehl, P. L. M. ( 1 999) Denovo protein design. II. Plasticity in sequence space. J . Mol. Biol.29 3 , 11 8 3 - 119 3 .

55. Kraemer-Pecore, C. M. , Lecomte, J. T. , and Desjarlais, J. R. (200 3 ) A de novo redesign of the ww do-main. Protein Sci. 1 2, 2194-2205.

56. Larson, S. M. , England, J. L. , Desjarlais, J. R. , and Pande, V. S. (2002) Thoroughly sampling sequencespace: large-scale protein design of structural ensembles. Protein Sci. 1 1 , 2804-2813.

57. Hayes, R. J. , Bentzien, J. > Ary, M. L. , Hwang, M. Y. , Jacinto, J. M. , Vielmetter, J. , Kundu, A. , and Dahiyat, B. I. (2002) Combining computational and experimental screening for rapid optimization of protein properties.Proc. NatL Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15926-15931.

58. Zou, J. and Saven, J. G. (2000) Statistical theory of combinatorial libraries of folding proteins: energetic discrim-ination of a target structure. J . Mol, Biol. 29 6, 28 1-29 4.

59. Kono, H. and Saven, J. G. (200 1 ) Statistical theory for protein combinatorial libraries. Packing interactions,backbone flexibility, and the sequence variability of a main-chain structure. J . Mol. Biol. 3 0 6 , 607-628.

60. Dunbrack, R. and Cohen, F. E. ( 1 997) Bayesian statistical analysis of protein side-chain retainer preferences.Protein Sci. 6, 1661 - 16 8 1 .

61. McQuarrie, D. A. ( 1 97 6 ) Statistical mechanics. Harper and Row, New York.

62. Press, W. H. , Teukolsky, S. A. , Vetterling, W. T. , and Flannery, B. P. (1 992) Nurnerical recipes.2nd e d .,Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

63. Weiner, S. J. , Kollman, P. A. , Case, D. A. , et al. ( 1 98 4 ) A new force field for molecular mechanical simula-tion of nucleic acids and proteins. J . Am. Chem. Soc. 1 0 6 , 765- 784.

64. Kono, H. and Doi, J. ( 1 99 6 ) A new method for side-chain conformation prediction using a hopfield network andreproduced rotamers. J . Comput. Chem. 1 7, 1667-1683.

65. Wernisch, L. , Hery, S. , and Wodak, S. J. (2000) Automatic protein design with all atom force-fields by exactand heuristic optimization. J . Mol, Biol. 3 0 1 , 7 13-736.

66. Sander, C. and Schneider, R. ( 1 99 1 ) Database of homology- derived protein structures and the structural meaningof sequence alignment. Proteins 9, 56-68.

67. Jensen, L. J. , Andersen, K. V. , Svendsen, A. , and Kretzschmar, T. ( 1 998) Scoring functions for computa-tional algorithms applicable to the design of spiked oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res,2 6 , 697-702.

68. Wolf, E. and Kim, P S. (1 999) Combinatorial codons j a computer program to approximate amino acid probabili-ties with biased nucleotide usage. Protein Sci. 8, 680-688.

69. Wang, W. and Saven, J. G. (2002) Designing gene libraries from protein profiles for combinatorial protein exper-iments. Nucleic Acids Res. 3 0, e 120.

70. Eriksson, A. E. , Baase, W. A. , Zhang, X. J. , Heinz, D. W. > Blaber, M. , Baldwin, E. P? , and Matthews,B. W. (1 992) Response of a protein structure to cavity-creating mutations and its relation to the hydrophobiceffect. Science 2 55, 178-183.

71. Axe, D. D. , Foster, N. W. ? and Fersht, A. R. ( 1 99 6 ) Active barnase variants with completely random hydrophobic cores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Scu USA 9 3 , 5590-5594.

72. Voigt, C. A. , Mayo, S. L. , Arnold, F. H. , and Wang, Z. G. (200 1 ) Computational method to reduce thesearch space for directed protein evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3778-3783.

1.1 蛋白质设计

通过对蛋白质结构(包括那些具有特殊功能结构)的设计,研究者可以増进对决定蛋白质折叠状态特征的力和效应的理解。另外,对特定折叠结构设计的控制,可能得到新的具有生物效能和特异性的合成蛋白。这样的应用包括在医药、传感器、催化剂和材料等领域。甚至在尚未完全和定量地理解决定蛋白质结构的力的条件下,蛋白质设计仍有可能取得成功。

但是,由于决定蛋白质折叠态的相互作用的复杂性和精细性,蛋白质设计不是一件轻而易举的事。蛋白质是巨大的分子(含数十到数百个氨基酸残基),折叠态的给定需要许多的结构变量,其中包括序列、主链拓扑和侧链构象。即使主链结构已经给定,每个残基仍可能有多重构象。除了结构的复杂性之外,还有序列的复杂性。设计意味着从无数的可能的序列中,鉴别出可折叠的序列。在折叠蛋白中观察到的高度“一致性” 引导这个搜索过程 [1] 。一般来说,处于折叠状态的蛋白质,在原子水平上,通过有利的范德华相互作用、疏水残基与溶剂隔离,并使大多数氢键作用都被满足而恰当地堆积。但这种一致性通常都是复杂的,可能没有什么能使问题简化的对称性。另外,精确地定量非共价相互作用属于最困难的一类问题,并且,估计残基替换或结构有序化的自由能,仍然是计算研究中最深奥的领域 [ 2,3 ] 。与预测能力相反,目前,我们还不能期望用详细的模拟估计自由能变化的方法,来确定大量序列的相对稳定性变化。尽管如此,从小分子和蛋白质数据库导出的分子位能,确实包含了已知的,对决定蛋白质结构起重要作用的,相互作用和力的部分信息。在某些情况下,这些位能的优化,已经在蛋白质设计中获得显著的成功 [ 4 ] 。这样的位能肯定是近似的,并且这样设计的任何序列,很可能对特定的位能和采用的目标结构敏感。作为另一种选择,在这些位能中包含的部分信息也可以做概率性的应用,以得到出现某种氨基酸的可能性。概率性方法也适合于确定可折叠到同一结构序列的完整可变性,因为似乎存在大量这样的序列—— 远大于可以用序列搜索或列举方式所能处理的。

这样的概率性方法也特别适合于在蛋白质组合实验中的全新设计,这些实验能产生并快速测试许多序列。虽然组合方法能处理大量序列(104~1012 ) ,但这些数量与可 能的蛋白质序列数比较仍然是无穷小,如对 100 个残基的蛋白质,这个数是 20100≈10130 ( 为了对 10130 这个数有多大有个一般的了解,假定合成出一条 100 个残基的蛋白质序列约需要 10000 /N g 物质,N≈6 X 1023,是阿伏伽德罗常数,那么合成出 10130 条序列需要超过 10107 kg 的物质。这个数量远超过目前我们所知宇宙物质的总质量 1035 kg一一译者注)。于是,即使是采用组合法,我们仍然必须集中于序列空间选定的一小部分。通过预先观察,在蛋白质中选定若干残基位点并在这些选定的位点允许残基的全部或部分可变性(全部可变性,即可以替换为 20 种氨基酸中任何残基;部分可变性, 只替换为某些类型的残基—— 译者注)来实现对序列空间的限定。近来发展了可以在宽得多的范围内追踪序列可变性,并提供扫视和聚焦序列空间的定量计算方法。在这里, 我们讨论序列设计的计算方法,把重点放在处理给定结构位点特异氨基酸可变性的概率方法。

1.2 蛋白质设计的定向方法

这里的 “定向蛋白质设计”是指鉴定出一条(或一组)可能折叠为预先指定的主链结构的序列。然后可以用多肽合成或基因表达的办法,实验性地实现每一条这样的序列,以确认其折叠态及其他分干性质。早期的设计努力,是在已观察到的自然发生的结构和已被确认的蛋白质序列的指导下完成的,它们有着重要的二级结构,但并不必 有明确的三级结构 [ 5 ] 。由于能够定量化并以表格列出残基间相互作用,计算方法已经极大地加速了蛋白质设计的成功率。典型情况下,这样的方法使序列搜索成为优化过程,在过程中改变氨基酸身份和侧链构象,以优化定量化序列结构相容性的打分函数, 对所有 mN 个可能序列的完全搜索,只有仅仅少量的残基 N 是允许改变的,或允许改变的氨基酸数目显著地减少,如从 m=20 减少到 m=2 时才是可行的。为了达到从内部平均来看有利的原子间相互作用的合理堆积序列,必须搜索每个氨基酸的不同侧链构象(旋转异构态)(见参考文献 [6])。结果,因为一个残基所可能有的状态数 m 增加 10 倍或更多—— 这取决于每个残基的旋转异构态数目和增加搜索的复杂性。如果只有很少的残基被允许改变,并且剩下的残基的构象受到限制,就可以对所有可能的组合完成完整数值计算,以鉴别出低能量的序列旋转异构态组合。由于(这个组合数)对链长和旋转异构态数目的指数依赖性,这样的完整数值计算在典型的情况下不能实现。在这样的情况下,序列空间可以用定向的方式取样以逐渐朝优化的(或部分优化的)序列方向移动。随机方法,如遗传算法和模拟退火,包含对序列空间的部分随机式搜索。在这种搜索中,搜索逐渐地移向髙分(低能)序列 [ 7~10 ] 。这样的搜索有足够的“噪声” 或重组,以允许越过序列-旋转异构地形图的局部极小值。当运用于精细到原子的表象中时,随机方法基本上集中于用疏水残基重新堆积结构的内部 [9] ,并已被用于 434 Cro、G 蛋白的 B1 结构域、WW 结构域和螺旋束的野生型结构。虽然在许多情况下这些方法对鉴别出实验可行的序列 [4,15 ] 有帮助,但是随机搜索法不必鉴别出整体优化点 [16] 。对只含有位点和对相互作用的位能,通过排除法,如 “死点排除法”,能找到整体优化点 [ 16~20 ]。这样的方法可连续地移除不可能是整体优化点的氨基酸-旋转异构态,直到再没有态可被移除。Mayo 研究组应用这一方法,已使拟 28 残基锌指蛋白 [21] 和在疏水和极性位点模式化之后的 51 残基同源域蛋白模体 [22] 的完整序列设计自动化。该组还重新设计了数种蛋白质内的部分残基组 [ 23~25 ] 。其功能性质,如结合金属或催化,也可以包括作为设计过程的元素 [ 26~28] 。蛋白质定向设计的要素和算法是最近一些综述的主体 [4,29,30 ] 。

尽管取得了某些惊人的成功,但序列定向设计的计算方法在鉴别折叠为特定结构的蛋白质序列特征上仍有局限性。随机方法可用于大蛋白,也容许多位点上的同时变化,但是,即使用于小蛋白,这样的计算消耗的机时和资源也是巨大的。定向方法对于使用的能量或打分函数必定是敏感的,因为它能鉴定能量函数的优化点。但是,所有这样的函数也必定是近似的,并且能量函数中的不确定因素可能不允许对整体优化点的搜索。许多天然存在的蛋白质是没有优化的。实际上,多数蛋白质只有微小的折叠稳定性,如 △G° < 10 kcal/mol [31] 。更有甚者,在功能上与其他分子结合的序列在结构稳定性上不必是整体优化的。重要的是发展与定向蛋白设计互补的方法,这些方法揭示可能折叠为某特定结构但又可能在结构上有未被优化的序列的特征。这样的技术可用于设计蛋白质序列。另外,这样的计算方法还可用于新型的蛋白质设计研究——组合式实验,即实验中大量蛋白质可以同时合成和筛选。

1.3 蛋白质设计的概率性方法

在蛋白质涉及的范围内,我们用定点氨基酸概率而不是特定的序列来描述“概率性蛋白质设计”。相对于定向的或决定论方法,概率性方法是常用于对问题只有部分信息场合的定量科学。对蛋白质设计,折叠过程的复杂性和不确定性促成了这样的概率性方法。蛋白质折叠是一个复杂的动态过程,有无数的相互作用规定折叠状态。每一个导致稳定的非共价键相互作用在大小上都是可以相互比较的,似乎没有哪一个具有压倒优势,以致于在折叠中起决定作用。定量化这些相互作用的办法,必定是近似的(见注 1 )。概率性设计方法也直接提供非常有用的序列信息,特别是在结构上重要的氨基酸。氨基酸概率可以引导特定序列的设计,也能够凸显能容忍突变、对结构只有微小影响的位点;在几轮蛋白质设计之后,这样的位点可以成为用来改变的目标。

概率性方法可以以几种方式应用于蛋白质设计。序列应该以符合计算出的概率方式生成。首先,最直接的选择是一个共用序列,或在每一个位点用最可能的氨基酸组成的序列。在必要时,可以重复地计算,逐次地增加蛋白质中(已经确定的)的残基。用这样的方法,已得到 114 个残基的双核金属蛋白 [32] 和一个完整膜蛋白的可溶性变体 [33] 。其次,计算概率可用于引导对序列的搜索,已提出基于 Monte Carlo 的方法。在 Monte Carlo 轨道的每一点决定序列的接受或拒绝时,计算的氨基酸概率用作有倾向性的选择标准 [ 34 ] 。用这样的方法处理相关的氨基酸身份,但要付出用于搜索的计算运转开销, 如果有信息可用于搜索,开销可以减少。最后,概率性方法可以用来定量地指导蛋白质组合库的设计 [ 35 ]。

1.4 组合实验

组合的蛋白质实验可以用来研究序列结构相容性和发现折叠为特定结构的新序列。在蛋白质组合设计实验中,筛选大量的序列(实物库),以找到以折叠为预先确定结构的迹象。取决于序列的离散性是如何产生和检验的,这类实验可以探测大量序列序列数可高达 1012 [36] 。可以用选择性分析,如配体结合或催化活性筛选序列(实物)库。以序列离散程度受研究者控制的方式,这样的实验可以“超越蛋白质序列数据库”。由于去掉了与天然蛋白进化压力的耦合,可以研究对折叠(和其他生物学性质)重要的特征。组合方法已用于鉴别螺旋蛋白 [ 37~39 ] 、泛素变体 [40]、单层自组装蛋白 [41]、具有纤维样性质的蛋白 [42] 以及稳定的寡聚螺旋 [ 43 ]。最近发表了几篇出色的关于组合实验和方法的综述 [44~47]。

1.3 注

1. 自洽的方法对整体优化不是最好的 [16] 。对蛋白质设计,这通常是因为在类平均场理论中处理残基身份和构象态之间相关的近似方式,随机取样和排除法常提供较好的结果。

2. 在设计序列时,主链柔性必须考虑。在天然蛋白质中,主链的微小调整会导致突变 [ 70,71 ]。但是,大多数计算方法把主链处理为刚性的,因为包括进柔性要消耗大量计算资源。统计理论的概率特性提示其预测剖面对主链选择较不敏感。当能量(或有效温度),在热容量 Cv 的峰值 [59] 之上,从蛋白 L 的 21 个稍有差别的主链结构得到的氨基酸剖面都相似。对微小的结构涨落均方差为 1A 紧密相关的序列特性会出现在 Ec 值达到或高于这个热容量峰值时。

3. 在完成熵受限制的优化时,我们发现利用这些方程的寻根法与限制性极小化算法表现得同样好。

4. 氨基酸的计算概率也可以用来计算对突变的容忍度。这样的突变在体外的定向蛋白进化实验 [72] 中在具有宽泛的氨基酸分布位点(在这些位点上许多氨基酸具有与最可能的氨基酸可比较的概率)最容易积累。

参考文献

1. Go, N. ( 1 98 3 ) Theoretical studies of protein folding. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1 2, 183-210.

2. Shea, J. E. and Brooks, C. L. 3rd. (200 1 ) From folding theories to folding proteins: a review and assessment ofsimulation studies of protein folding and unfolding. Anrvu. Rev, Phys. Chem. 5 2, 499-535.

3. Brooks, C. L. 3rd. (2002) Protein and peptide folding explored with molecular simulations. Acc. C/iem. 35,447-454.

4. Kraemer-Pecore, C. M. , Wollacott, A. M. , and Desjarlais, J. R. ( 2 0 0 1 ) Computational protein design.Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 5 , 690-695.

5. Bryson, J. W. , Betz, S. F. , Lu, H. S. , et al. ( 1 99 5 ) Protein design: a hierarchic approach. Sczenc^ 270,935-941.

6. Dunbrack, R. (2002) Rotamer libraries. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1 2, 431-440.

7. Shakhnovich, E. I. and Gutin, A. M. ( 1 99 3 ) A new approach to the design of stable proteins. Protein Eng. 6 ,793- 800.

8. Jones, D. T. ( 1 99 4 ) De novo protein design using pairwise potentials and a genetic algorithm. Protein Sci. 3,567-574.

9. Hellinga, H. W. and Richards, F. M. ( 1 99 4 ) Optimal sequence selection in proteins of known structure by simu-lated evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9 1 , 5803-5807.

10. Desjarlais, J. R. and Handel, T. M. (1 99 5 ) De novo design of the hydrophobic cores of proteins. Protein Sci. 4 ,2006-2018.

11. Johnson, E. C. , Lazar, G. A. , Desjarlais, J. R. , and Handel, T. M. ( 1 999) Solution structure and dynam-ics of a designed hydrophobic core variant of ubiquitin. Struct. Fold. Des.7, 967-976.

12. Jiang, X ., Farid, H. , Pistor, E. , and Farid? R. S. (2000) A new approach to the design of uniquely foldedthermally stable proteins. Protein Sci.9, 403-416.

13. Jiang, X. , Bishop, R J. , and Farid, R S. ( 1 997) A 办 wcrlo designed protein with properties that characterize natu_ral hyperthermophilic proteins. /. Am. Chem. Soc. 11 9, 838, 839.

14. Bryson, J. W. , Desjarlais, J. R. , Handel, T. M. and DeGrado, W. F. ( 1 998) From coiled coils to smallglobular proteins: design of a native-like three-helix bundle. Protein S ci. 7 , 14 04-1414 .

15. Walsh, S. T. R. , Cheng, H. , Bryson, J. W. , Roder, H. , and DeGrado, W. F. ( 1 999) Solution structure anddynamics of a de novo designed three-helix bundle protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9 6, 5486-5491.

16. Voigt, C. A. , Gordon, D. B. , and Mayo, S- L. (2000) Trading accuracy for speed: a quantitative comparison ofsearch algorithms in protein sequence design. J . Mol. Biol.299, 789-803.

17. Gordon, D. R and Mayo, S L. (1998) Radical performance enhancements for combinatorial optimization algorithms basedon the dead-end elimination theorem. /. Comput. Cherru 19, 1505-1514.

18. Gordon, D. B. and Mayo, S. L. (1 999) Branch-and terminate: a combinatorial optimization algorithm for proteindesign. Struct, Fold. Des. 7, 1089-1098.

19. Pierce, N. A. , Spriet, J. A. , Desmet, J. , and Mayo, S. L. (2000) Conformational splitting: a more powerfulcriterion for dead-end elimination. /. Comput. Chem. 2 1 , 999-1009.

20. Looger, L. L. and Hellinga, H. W. (200 1 ) Generalized dead-end elimination algorithms make large-scale proteinside-chain structure prediction tractable: implications for protein design and structural genomics. J . Mol. Biol. 307,429-445.

21. Dahiyat, B. I. and Mayo, S. L. ( 1 997) De novo protein design: fully automated sequence selection. Science 278,82-87.

22. Marshall, S. A. and Mayo, S. L. (200 1 ) Achieving stability and conformational specificity in designed proteins viabinary patterning. J . Mol. Biol. 30 5 , 619-631.

23. Malakauskas, S. M. and Mayo, S. L. ( 1 998) Design, structure, and stability of a hyperthermophilic protein vari-ant. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5 , 470-475.

24. Strop, P. and Mayo, S. L. ( 1 999) Rubredoxin variant folds without iron. J . Am. Chem. Soc. 1 2 1 , 2 341-2 345 .

25. Shimaoka, M. , Shifman, J. M. , Jing, H. , Takagi, L. , Mayo, S. L. , and Springer, T. A. (2000) Computa-tional design of an integrin i domain stabilized in the open high affinity conformation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7,674-678.

26. Benson, D. E. , Wisz, M. S. 9 Liu, W. , and Hellinga, H. W. ( 1 998) Construction of a novel redox protein byrational design: conversion of a disulfide bridge into a mononuclear iron-sulfur center. Biochemistry 37,7070-7076.

27. DeGrado, W. F .,Summa,C. M . , Pavone,V . ,Nastri,F . , and Lombardi,A. (1 999) De novo design andstructural characterization of proteins and metalloproteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 6 8, 779-819.

28. Bolon, D. N. and Mayo, S. L. (200 1 ) Enzyme-like proteins by computational design. Proc. NatL Acad. Sci. USA98, 14 27 4 - 14 279.

29. Street, A. G. and Mayo, S. L. (1 999) Computational protein design. Struct. Fold. Des.7, R 105-R 109.

30. Saven, J. G. (200 1 ) Designing protein energy landscapes. Chem. Rev. 1 0 1 , 3113-3130.

31. Gromiha, M. M. , Uedaira, H. , An, J. , Selvaraj, S. ? Prabakaran, P. , andSarai, A. (2002) Protherm, ther-modynamic database for proteins and mutants: developments in version 3. 0. Nucleic Acids Res. 3 0, 301> 302.

32. Calhoun, J. R. , Kono, H. , Lahr, S. , Wang, W. , DeGrado, W. F. , and Saven, J. G. (200 3 ) Computationaldesign and characterization of a monomeric helical dinuclear metalloprotein. J . Mol. Biol. 334, 11 0 1 - 1115 .

33. Slovic, A. M. , Kono, H. , Lear, J. D. , Saven, J. G. , and DeGrado, W. F. (200 4) Computational design of wa-ter-soluble analogues of the potassium channel kcsa. Proc, Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1 0 1 , 1828-1 833.

34. Zou, J. and Saven, J. G. (200 3) Using self-consistent fields to bias monte carlo methods with applications to desig-ning and sampling protein sequences. J. Chem, Phys. 1 1 8 , 3843-3854.

35. Park, S. , Kono, H. , Wang, W. , Boder, E. T. , and Saven, J. G. (200 5) Progress in the development and ap-plication of computational methods for probabilistic protein design. Comp. Chem, Eng. 2 4 , 407-421.

36. Keefe, A. D. and Szostak, J. W. (2 0 0 1 ) Functional proteins from a randomsequence library. Nature 41 0,715-7 1 8.

37. Rojas, N. R. L. , Kamtekar, S. , Simons, C. T. , et al. .(1 997) Denovo heme proteins from designed combinato-rial libraries. Protein Sci. 6 , 2 512-2524.

38. Roy, S. , Ratnaswamy, G. , Boice, J. A. , Fairman, R. , McLendon, G. , and Hecht, M. H. (1 997) A proteindesigned by binary patterning of polar and nonpolar amino acids displays native-like properties.J.A m . Chem, Soc. 11 9 , 5302-5306.

39. Roy, S. , Helmer, K. J. , and Hecht, M. H. (1 997) Detecting native-like properties in combinatorial libraries ofde novo proteins. Fold. Des. 2, 89-92.

40. Finucane, M. D. , Tuna, M. , Lees, J. H. , and Woolfson, D. N. ( 1 999) Core-directed protein design. I. An ex-perimental method for selecting stable proteins from combinatorial libraries. Biochemistry 3 8, 11 > 6 0 4 , 1 1 ,612.

41. Xu, G. F. , Wang, W. X. , Groves, J. T. , and Hecht, M. H. (200 1 ) Self-assembled monolayers from a designedcombinatorial library of denovo beta-sheet proteins. Proc. Natl, Acad. Sci, USA 98, 3652-3657.

42. Case, M. A. and McLendon, G. L. (2000) A virtual library approach to investigate protein folding and internalpacking. J . Am. Chem. Soc. 1 2 2, 8089, 8090.

43. Arndt, K. M. , Pelletier, J. N. , Muller, K. M. , Alber, T. , Michnick, S. W. , and Pliickthun, A. (2000) Aheterodimeric coiled-coil peptide pair selected in vivo from a designed library-versus-library ensemble./. Mol. Biol.29 5 , 627-639.

44. Zhao, H. M. and Arnold, F. H. ( 1 997) Combinatorial protein design: strategies for screening proteinlibraries. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 480— 485.

45. Giver, L. and Arnold, F. H. ( 1 9 9 8 ) Combinatorial protein design by in vitro recombination. Curr. Opin.Chem. Biol.2, 335-338.

46. Hoess, R. H. (200 1 ) Protein design and phage display. Chem.Rev. 1 0 1 > 3205-3218.

47. Moffet, D. A. and Hecht, M. H. ( 2 0 0 1 ) De novo proteins from combinatorial libraries. C/iem. 1 0 1 ,3191-3 203 .

48. Holm, L. and Sander, C. (1 998) Touring protein fold space with dali/fssp. Nucleic Acids Res. 2 6 , 316-319.

49. Luthy, R. , Bowie, J. U. , and Eisenberg, D. ( 1 992) Assessment of protein models with 3-dimensional pro-files. Nature 356, 83-85.

50. Durbin, R. , Eddy, S. , Krogh, A. , and Mitchison, G. ( 1 998) Biological Sequence Analysis ?. ProbabilisticModels o f Proteins and Nucleic Acids,Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

51. Raha, K. , Wollacott, A. M. , Italia, M. J. , and Desjarlais, J. R. (2000) Prediction of amino acid sequence fromstructure. Protein S ci. 9 9 11 0 6 - 111 9.

52. Kuhlman, B. and Baker, D. (2 0 0 0 ) Native protein sequences are close to optimal for their structures.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, USA 97, 10383-10388.

53. Koehl,P.L .M . (1 9 9 9 ) De novo protein design. I. In search of stability and specificity. J . MoZ. BzoZ. 2 3 9,1161 - 11 8 1 .

54. Koehl, P. L. M. ( 1 999) Denovo protein design. II. Plasticity in sequence space. J . Mol. Biol.29 3 , 11 8 3 - 119 3 .

55. Kraemer-Pecore, C. M. , Lecomte, J. T. , and Desjarlais, J. R. (200 3 ) A de novo redesign of the ww do-main. Protein Sci. 1 2, 2194-2205.

56. Larson, S. M. , England, J. L. , Desjarlais, J. R. , and Pande, V. S. (2002) Thoroughly sampling sequencespace: large-scale protein design of structural ensembles. Protein Sci. 1 1 , 2804-2813.

57. Hayes, R. J. , Bentzien, J. > Ary, M. L. , Hwang, M. Y. , Jacinto, J. M. , Vielmetter, J. , Kundu, A. , and Dahiyat, B. I. (2002) Combining computational and experimental screening for rapid optimization of protein properties.Proc. NatL Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15926-15931.

58. Zou, J. and Saven, J. G. (2000) Statistical theory of combinatorial libraries of folding proteins: energetic discrim-ination of a target structure. J . Mol, Biol. 29 6, 28 1-29 4.

59. Kono, H. and Saven, J. G. (200 1 ) Statistical theory for protein combinatorial libraries. Packing interactions,backbone flexibility, and the sequence variability of a main-chain structure. J . Mol. Biol. 3 0 6 , 607-628.

60. Dunbrack, R. and Cohen, F. E. ( 1 997) Bayesian statistical analysis of protein side-chain retainer preferences.Protein Sci. 6, 1661 - 16 8 1 .

61. McQuarrie, D. A. ( 1 97 6 ) Statistical mechanics. Harper and Row, New York.

62. Press, W. H. , Teukolsky, S. A. , Vetterling, W. T. , and Flannery, B. P. (1 992) Nurnerical recipes.2nd e d .,Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

63. Weiner, S. J. , Kollman, P. A. , Case, D. A. , et al. ( 1 98 4 ) A new force field for molecular mechanical simula-tion of nucleic acids and proteins. J . Am. Chem. Soc. 1 0 6 , 765- 784.

64. Kono, H. and Doi, J. ( 1 99 6 ) A new method for side-chain conformation prediction using a hopfield network andreproduced rotamers. J . Comput. Chem. 1 7, 1667-1683.

65. Wernisch, L. , Hery, S. , and Wodak, S. J. (2000) Automatic protein design with all atom force-fields by exactand heuristic optimization. J . Mol, Biol. 3 0 1 , 7 13-736.

66. Sander, C. and Schneider, R. ( 1 99 1 ) Database of homology- derived protein structures and the structural meaningof sequence alignment. Proteins 9, 56-68.

67. Jensen, L. J. , Andersen, K. V. , Svendsen, A. , and Kretzschmar, T. ( 1 998) Scoring functions for computa-tional algorithms applicable to the design of spiked oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res,2 6 , 697-702.

68. Wolf, E. and Kim, P S. (1 999) Combinatorial codons j a computer program to approximate amino acid probabili-ties with biased nucleotide usage. Protein Sci. 8, 680-688.

69. Wang, W. and Saven, J. G. (2002) Designing gene libraries from protein profiles for combinatorial protein exper-iments. Nucleic Acids Res. 3 0, e 120.

70. Eriksson, A. E. , Baase, W. A. , Zhang, X. J. , Heinz, D. W. > Blaber, M. , Baldwin, E. P? , and Matthews,B. W. (1 992) Response of a protein structure to cavity-creating mutations and its relation to the hydrophobiceffect. Science 2 55, 178-183.

71. Axe, D. D. , Foster, N. W. ? and Fersht, A. R. ( 1 99 6 ) Active barnase variants with completely random hydrophobic cores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Scu USA 9 3 , 5590-5594.

72. Voigt, C. A. , Mayo, S. L. , Arnold, F. H. , and Wang, Z. G. (200 1 ) Computational method to reduce thesearch space for directed protein evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3778-3783.