燕麦转基因及其在提高渗透胁迫耐受中的应用

丁香园

7337

1. 引言

燕麦(Avena sativa L. ) 是一种冷季型一年生禾谷类作物,其全球产量位于小麦、玉米、水稻、大麦、高粱和小米之后,为世界第七大禾谷类作物。不同于其他禾谷类作物,绝大多数的燕麦在国内流通消耗,只有少量出口贸易 [1,2 ] 。燕麦喜好较冷和潮湿的气候,能够在不同类型的土壤上生长 [3,4]。其生长相比小麦和大麦来说,能适应更大范围的土壤 pH,如 pH 从 5.5~7.0,有些燕麦品种甚至可以在 pH 4.5 的土壤上生长。另外,燕麦种植的土壤石灰施用量很低 [5],但是其生长和结实需要充足的水分。因此,俄罗斯、加拿大、美国、芬兰和波兰是主要的燕麦生产国 [6 ]。而燕麦最高的产量一般来自新西兰、瑞士、德国、英国、爱尔兰、瑞典和法国等国 [7]。

因为燕麦的蛋白质和必需矿物质含量高,几个世纪以来,一直是优良的家畜伺料[ 8 ]。另外,燕麦的高纤维含量能促进消化 [ 6 ]。燕麦也可用于食品加工,如燕麦片、燕麦淀粉和饼干。近来燕麦和燕麦麸作为健康食物也大受欢迎,因为其能够帮助减少血液中的胆固醇,并且能够调节胃肠功能 [6 ]。最近燕麦更是被用于化妆品生产,因为其含有两种活性成分—— 燕麦生物碱和葡聚糖。这两种物质有利于保护皮肤,用于抵抗刺激物和帮助晒伤的皮肤再生等。燕麦还可用于造纸和酿造工业,以及用来生产塑料、杀虫剂和防腐剂 [7]。燕麦还可作为伺料、牧草,用于生产绿肥,或作为作物覆盖物。作为作物覆盖物时,燕麦能够延长土壤使用寿命,抑制杂草生长,控制土壤的侵蚀和增加有机成分 [4,8]。以上原因直接导致了对优质燕麦需求的增加。

环境胁迫,如干旱和盐碱,限制了全球农业产量 [9,10]。尤其是盐碱,影响了全球约 1/3 的灌溉农业用地 [11, 12]。由于不合理的耕作,世界可耕地面积正在逐渐减少 [13]。这使得农民不得不在容易发生盐碱的地区种植和收获受盐胁迫的农作物[14] 。燕麦对高温和干旱的气候很敏感,其产量依赖于生长季节中供水量是否充足

[15] 。燕麦对盐胁迫的适应性还知之不多,但一般认为其对盐胁迫的耐受性要比其他的谷类或伺料作物低 [16]。有报道称盐害能够降低不同燕麦品种种子的萌发率和影响萌发后的生长 [16, 17]。倒伏是影响燕麦产量的另一个因素。同时,燕麦也易受大麦黄条矮缩病毒和有害昆虫的影响 [18,19]。人们已经对燕麦品种进行了改良,以提高其抗病性,但规模有限 [20]。

由于不同燕麦品种间基因组背景的保守性及低效的选育方法,人们难以通过传统育种手段来解决燕麦生产中的问题 [21]。但是,现代作物改良策略,如生物技术,可以与传统育种手段相结合来促进农业增产 [22~24]。生物技术作为一种具有良好前景的方法,不仅可解决发展中国家面临的有限的作物产量的问题,而且能促进可持续农业的发展 [25, 26 ]。因此,选择具有髙产遗传潜力的品种,或通过遗传工程手段培育抗性品种,有助于提高胁迫条件下燕麦的产量水平。

最近,禾谷类作物的改良得益于组织培养和优良性状基因的遗传工程改良 [27~29 ]。但是,关于不受基因型影响的燕麦体外再生和基因工程体系的研究报道仍然有限 [29~34]。1996 年,张等发展了一种不受基因型影响的高效的茎尖分生组织再生体系,可用于商业化燕麦品种的遗传转化 [35]。其后的研究报道了基因枪介导的转化体系,

应用成熟胚来源的愈伤 [36,37]、幼苗叶基部 [ 38 ] 和未成熟胚来源的胚性愈伤组织作为受体进行遗传转化 [39]。但是,胚源性愈伤不适于常规的燕麦转化,因为延长组织培养时间可能造成体细胞无性系的变异 [40,41]。因此,来自成熟种子的多芽分生组织,可作为另一种不受基因型影响的具有再生能力的受体组织,用于商业化燕麦品种的遗传转化 [35~47]。采用这一体系,可以高效地进行组织再生且重复性好,获得的转基因植株具有很高的结实率和基因组稳定性。

这里,我们介绍了茎尖分生组织结合基因枪介导,对三个燕麦品种进行遗传转化的方法,以及利用该方法转化抗渗透胁迫基因 hva1,提高燕麦对渗透胁迫的耐受性。此外 ,我们还介绍了对转基因燕麦的分子和生化分析,以证实转基因的整合,表达稳定并可遗传,同时检测了 hva1 基因在转基因植株中的表达及其对盐碱和缺水的耐受性的影响。

2. 材料

2.1 燕麦品种

(1) Ogle ( Brave/2/Tyler/Egdoion23 )

(2) Pacer (CoachmanxCI 1382)

(3) Prairie(IL73-5743xOgle)

2.2 质粒

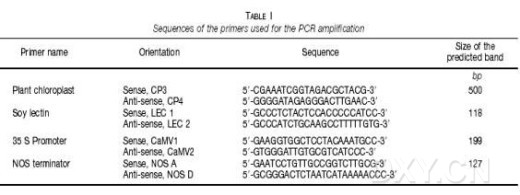

(1) pBY520 包含两个基因:一个是来源于 Streptomyces hygroscopicus 的抗除草剂基因 —— 草胺膦乙酰基转移酶基因(bar),作为选择标记,该基因由花椰菜病毒启动子(CaMV35S ) 驱动,以农杆菌胭脂氨酸合成酶基因(nos ) 的 3' 非编码区为终止子。胁迫抗性基因来源于大麦胚胎发生后期的富集蛋白基因(Shva1) ,由水稻肌动蛋白 Act1 的启动子驱动,以马铃薯蛋白水解酶抑制子II ( pin ll ) 的 3' 非编码区为终止子( 图 10.1) 。

(2) pAct1-D:含有由 Act1 启动子驱动并利用 nos 终止子的大肠杆菌 β-葡萄糖醛酸酶基因(gus) ( 图 10.1 )。

2 . 3 培养基

( 1 ) MS1 ( 萌发培养基):4.3 g/L MS [ 52 ] 基本培养基和维生素(GIBC0 BRL Rockville,Maryland ) ,30 g/L蔗糖( Sigma,St. Louis,MO, USA ) ,3 g/L phytagel (Sigma), pH 5.6。

( 2 ) MS2 ( 芽增殖培养基):MS 培养基,30 g/L 蔗糖,500 mg/L 酪蛋白酶水解物 (Sigma) , 0.5 mg/L 2,4-D (Sigma) , 2 mg/L N6- 芐基腺嘌呤(Sigma ) , 3 g/L phytagel,pH 5. 6。

( 3 ) MS3 ( 粒子轰击培养基):MS 培养基,30 g/L 蔗糖,500 mg/酪蛋白酶水解物(Sigma) ,0~5 mg/L 2,4-D ( Sigma) ,2 mg/L N6-芐基腺嘌呤(Sigma) ,5 g/L phytagel。

( 4 ) MS4(低选择压的芽增殖培养基):MS2 培养基,5 mg/L 草胺膦(Sigma) 或 2 mg/L 双丙氨膦(Meiji Seika Kaisha, Japan) 。

( 5 ) MS5(高选择压的芽增殖培养基): MS2 培养基,10 mg/L 草胺膦或 3 mg/L 双丙氨膦。

( 6 ) MS6(芽再生培养基):MS 培养基,20 g/L 蔗糖,0.5 mg/L N6-苄基腺嘌呤,0.5 mg/L B 吲哚三丁酸(Sigma) ,15 mg/L 草胺膦或 5 mg/L 双丙氨膦,3~5 g/L phytagel,pH 5.6。

( 7 ) MS7(生根培养基):2.15 g/L MS 培养基,10 g/L 蔗糖,15 mg/L 草胺膦或 5 mg/L 双丙氨膦,3~5 g/L phytagel,pH 5.8。

( 8 ) MS8(盐胁迫培养基):2.15 g/L MS 培养基,10 g/L 蔗糖,100 mmol/L NaCl (Sigma),3~5 g/L phytagel, pH 5.8。

( 9 ) MS9(渗透胁迫培养基):2.15 g/L MS 培养基,10 g/L 蔗糖,200 mmol/L manifold (Sigma) ,3~5 g/L phytagel, pH 5.8。

所有的培养基需 121℃ 高压蒸汽灭菌 20 min。激素、除草剂和抗生素在培养基灭菌后添加(40~50°C ) 。

2.4 其他材料

( 1 ) Clorox 漂白剂 (Clorox Professional Products Company, Oak- land, CA 94612)

( 2 ) 塑料植物盆(8 cm 方格,Griffin Green House and Nursery Supplies,1619 Main Street, Tewksbury, MA 01876)。泥炭和珍珠岩混合土 (Griffin Green House and Nursery Supplies)。

( 3 ) 混合土( Metro Mix 360 Soil; Griffin Green House and Nursery Supplies)

( 4 ) Ignite 含有 200 g/L ( 16. 222% ) 活性成分草胺膦的除草剂(1% Ignite Hoechst-Roussel Agri-Vet Company, NJ)

( 5 ) 蛋白提取缓冲液:50 mmol/L 磷酸钠缓冲液(pH 7.0 ) ,10 mmol/L EDTA(乙二胺四乙酸), 0.1% (V/V) Triton X-100,0.1% (m/V ) Sarkosyl,10 mmol/L 疏基乙醇,10 mmol/L PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride)。

( 6 ) 碱性磷酸酶缓冲液:100 mmol/L Tris-base,100 mmol/L NaCl,5 mmol/L MgCl2( pH 9.8 ) 含有 0.33 mg/ml NBT (Nitro blue tetrazolium ) ,0.16 mg/ml BCIP (5 - bromo - 4 -chloro-3 -indolyl phosphate)。

( 7 ) GUS底物:10 mmol/L EDTA ( pH 7.0 ) ,0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.0 ) ,1~5 mmol/L X-Gluc(X- Gluc 可以用二甲基亚砜溶解,Sigma)。

3. 注释

注 1 : 种子还可用 70% 乙醇消毒 2 min;用无菌蒸馏水洗一次,然后在 50% Clorox 漂白剂中浸泡 15 min,期间以 0.5 g 持续振荡。

注 2 : 用灭菌的滤纸汲取种子上的水分(3 mm;VWR) ,再将消毒后的种子放置于 MS1 培养基上。

注 3 : 芽尖包含有顶端分生组织、2~3 个叶原基和叶基。芽尖是靠近叶基的膨大部分。

注 4 : 每一品种放置 7~8 个皿。为获得不同品种的最佳效果,用不同浓度的 2 ,4 -D ( 0 mg/L 和 0.5 mg/L ) 和 N6-苄基腺嘌呤(0 mg/L、0.5 mg/L、1.0 mg/L 、2.0 mg/L、4.0 mg/L 和 8.0 mg/L ) 的组合。

注 5 : 计算丛生芽的相对分化频率(见 [47])。

注 6 : 为获得多个质粒转化的最佳结果,用不同质粒摩尔比,如 3 : 1 或 2 : 1 (两个质粒)、1 : 1 : 1 或 3 : 2 : 1 (三个质粒),带有选择标记的质粒是比值中的最后一个(即浓度最低)。

注 7 : 用由芽分生组织分化而来的、培养 1 个月的丛生芽培养物进行基因枪轰击转化 [ 图 10. 2 (a ) ] ; 如有必要,在轰击之前去除胚芽鞘和叶片使丛生芽外露。

注 8: 在 26 mmHg 气压下,用基因枪微粒加速装置(PDS 1000/He, Bio- Rad) 进行轰击,可裂膜到载体膜的距离为 1. 5 cm, 载体膜到终止屏的距离为 2 cm, 终止屏到样品的距离为 6. 5 cm, 氦气压为 1550 psi。

注 9 : 第一次轰击后,将组织放在 25℃ 暗培养直到第二次轰击。

注 10 : 在温室中生长 1 个月后,将植株移到大盆中(12 cm2) ,促进其生长; 如有必要,每周施用一次 Peters 20 : 20 : 20 的 肥 料(Griffin Green House and Nursery supplies)。

注 11 : 除草剂的使用:在三叶期最幼嫩的叶片上涂抹除草剂,到六叶期时对整个植株喷洒 1% Ignite 除草剂,草胺磷活性成分为 200 g/L( 16. 222% ) 。

注 12 : 用不同的转基因独立株系种子(R。、R1 或 R2)。在本实验中使用来自 5 个独立的转基因株系的 R2 代 Ogle BRA-82、 Ogle BRA-17、 Ogle BRA-8、 Ogle BRA-19 和 Ogle BRA-41。

注 13:将代转基因种子种植于 MS7 选择培养基上,以筛选转基因和非转基因的植株。选用在选择培养基上能够生长的苗,测试对胁迫的抗性。

注 14 : 植物鲜重:从 Magenta 盒中将整株植株小心取出,不要损伤生长于培养基中的根系,将根系上的培养基清洗掉,再用纸巾汲干,用天平称重(Precision Weighing Balances, Bradford, MA 01835)。

注 15 : 植物干重:将整株植株放入已称重的 3 mm 滤纸上,滤纸已经烘干至恒重。用铝箔包裹,置于 110℃ 恒 温箱中(VWR) 烘干 24 h。将样品从恒温箱取出放入干燥器中(VWR) ,避免称重前样品吸水。待其降至室温,称重后减去滤纸的质量,得出每一植株的质量。

注 16 : 在培养基中加入甘露醇,使离体条件下生长的植株产生缺水或渗透胁迫。

注 17 : 这是一个优化的方法,以评估表达 Ami 的转基因株系在温室中环境下对缺水胁迫的耐受性 [48]。

注 18: 5 个燕麦 Ogle 独立转基因株系 R3 代 BRA -8、 BRA-17、 BRA-19、 BRA- 41 和 BRA-82,由本研究中的 R2 代植株繁殖获得 [47],并与对照植株一起置于温室中生长。

注 19 : 每一盐溶液处理一组植株。每天浇灌一次,确保渗透完全,并防止盐过量。

注 20 : 还可进行其他性状的测定,如分蘖数、至抽穗的天数、剑叶叶面积、千粒重 、每穗结实率、花序长度、每个花序的小花数等 [48, 51] 。

4. 参考文献

1. Hitchcock, A. S. ( 1971) Manual of the grasses of the United States. Originally published in 1950 as U. S.D. A. Miscellaneous publication No. 200. Dover, New York. Second edition revised by Chase, A.

2. Munz, P. A. and Keck, D. D. (1973) A California Flora (with Supplement by P. Munz). University of

California Press, Berkeley, California.

3. Madson, B. A. (1 9 5 1 ) Winter Covercrops. Circular 17 4 , California Agricultural Extension Service,

College of Agriculture, University of California, June 1951.

4. Johnny 』 s selected seeds ( 1983) Green Manures-A Mini Manual. Johnny, s selected seeds, Albion,Maine 04910.

5. Verhallen, A . ,Hayes, A. and Taylor, T. (2003) Cover crops-Oats, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and

Rural Affairs, Ontario, Canada.

6. Gibson, L. and Benson, G. (2002) Origin, history, and uses of oat ( Avena sativa ) and wheat ( Triticum aestivum). Course Agronomy 212, Iowa State University, Department of Agronomy, Iowa.

7. http : //interactive, usask. ca/Ski/agriculture/crops/cereals/oats. html. Agriculture crops cereals oats.

Saskatchewan Interactive, last updated 14 Dec 2002.

8. Forsberg, R. A. and Shands, H. L. ( 1989) Oat breeding in Plant Breeding Reviews. Vol. 6 , (Janick, J . ,ed. ) , Timber Press, Portland, OR, pp 167-207.

9. Boyer, J. S. (1982) Plant productivity and environment. Science 218, 444-448.

10. Roy, M. and Wu, R. (2 0 0 2 ) Overexpression of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase gene in rice

increases polyamine level and enhances sodium chloride-stress tolerance. Plant Science 163, 987-992.

11. Apse, M. P . , Aharon, G. S ., Snedden, W. A. and Blumwald, E. (1999) Salt tolerance conferred by over expression of a vacuolar Na+/ H + antiport in Arabidopsis. Science 285, 1256-1258.

12. Schachtman, D. and Lui, W. ( 1999) Molecular pieces to the puzzle of the inLeraclion l)elween |) 〇 lassiurn and sodium uptake in plants. Trends in Plant Science 4 , 281-287.

13. Qadir, M ., Qureshi, H. H. and Ahmad, N. ( 1998) Horizonlal flushing : a promising ameliorative technology for hard salinesodic and sodic soils. Soil Tillage Research 4 5, 119-131.

14. Cherry, J. H ., Locy, R. D. and Rychter, A. (1999) Proc. NATO Adv. Res. Workshop, Mragowa, Poland. 13-19 June. Kluwer, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

15. Martin, R. J . , Jamieson, P. D ., Gillespie, R. N. and Maley, S. (2001) Effect of timing and intensity of drought on the yield of oats {Avena sativa L. ) . Proceeding of the 10th Australian Agronomy Conference,Hobart.

16. Murty, A. S ., Misra, P. N. and Haider, M. M. ( 198 4 ) Effect of different salt concentrations on seed germination and seedling development in few oat cultivars. Indian Journal o f Agricultural Research 18,129-132.

17. Verma, 0. P. S. and Yadava, R. B. R. (1986) Salt tolerance of some oats {Avena sativa L. ) varieties at germination and seedling stage. Journal o f Agronomy and Crop Science 156, 123-127.

18. Schonbeck, M. W. (1988) Cover Cropping and Green Manuring on Small Farms in New England and New York: An Informal Survey. Research Report 10, New Alchemy Institute, East Falmouth, MA 02536.

19. Koev, G ., Mohan, B. R ., Dinesh-Kumar, S. P ., Torbert, K. A., Somers, D. A. and Miller, W. A.

(1998) Extreme reduction of disease in oats transformed with the 5 5 half of the barley yellow dwarf virus PAV genome. Phytopathology 88, 1013-1019.

20. Stoskopf, N. C. (1985 ) Barley and Oat, in Cereal Grain Crops, (Stoskopf, N. C ., ed. ) , Reston Publishing , Reston, Virginia, pp. 444 -4 58.

21. Cushman, J. C. and Bohnert, H. J. (2000) Genomic approach to plant stress tolerance. Current Opinions in Plant Biology 3, 117-12 4.

22. Abebe, T ., Guenzi, A. C., Martin, B. and Cushman, J. C. ( 2003 ) Tolerance of mannitol-

accumulating transgenic wheat to water stress and salinity. Plant Physiology 131, 17 48-1755.

23. Epstein, E ., Norlyn, J . , Rush, D ., Kings-bury, R ., Kelley, D ., Cunningham, G. and Wrona, A.

(1980) Saline culture of crops : a genetic approach. Science 210, 399- 4 0 4 .

24. Ribaut, J. M. and Hoisington, D. A. (1998) Marker assisted selection : new tools and strategies. Trends in Plant Science 3, 236-239.

25. FAO. (1 9 9 9 ). Biotechnology in food and agriculture, http : //www. fao. org/unfao/ bodies/COAG/CO-AG15/X0074 E. htm.

26. Sharma, H. C ., Crouch, J. H ., Sharma, K. K ., Seetharama, N. and Hash, C. T. (2002) Application of biotechnology for crop Transformation of Oats and Its Application 167 improvement: prospects and constraints. Plant Science 163, 381-395.

27. Mazur, B ., Krebbers, E. and Tingey, S. ( 1999) Gene discovery and product development for grain quality traits. Science 285, 372-375.

28. Rines, H. W ., Phillips, R. L. and Somers, D. A. (1992) Application of tissue culture to oat improvement, in Oat Science and Technology, ( Marshall, H. G ., and Sorrels, M. E ., eds. ) , American Society of Agronomy and Crop Science Society, Madison WI, pp. 777-791.

29. Somers, D. A., Torbert, K. A., Pawlowski, W. P. and Rines, H. W. ( 199 4 ) Genetic engineering of oat, in Improvement of Cereal Quality by Genetic Engineering , (H en ry ,R. J. and Ronalds, J. A . ,ed s.), Plenum, New York, pp. 37-46.

30. Cummings, D. P . , Green, C. E. and Stuthman, D. D. ( 1976) Callus induction and plant regeneration in oats. Crop Science 16, 465-4 70.

31. Rines, H. W. and McCoy, T. J. ( 1981) Tissue culture initiation and plant regeneration in hexaploid species of oats. Crop Science 21, 837-8 42.

32. Bregitzer, P ., Bushnell, W. R ., Somers, D. A. andRines, H. W. (1989) Development and characterization of friable, embryogenic oat callus. Crop Science 29, 798-803.

33. Rines, H. W. and Luke, H. H. (1985) Selection and regeneration of toxin insensitive plants from tissue cultures of oat (Avena sativa) susceptible to Helminthosporium victoriae. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 7 1 , 16-21.

34. Somers, D. A., Rines, H. W ., Gu, W ., Kaeppler, H. F. and Bush-Nell, W. R. ( 1992) Fertile

transgenic oat plants. Bio/Technology 10, 1589-159 4.

35. Zhang, S. ^ Zhong, H. and Stickler!, M. B. (1996) Production of multiple shoots from apical meristems of oat (Avena sativa L. ). Journal o f Plant Physiology 1 4 8, 667-671.

36. Torbert, K. A ., Rines, H. W. and Somers, D. A. (1998) Transformation of oat using mature embryo-drived tissue cultures. Crop Science 38, 226-231.

37. Cho, M. J . , Jiang, W. and Lemaux, P. G. ( 1999) High frequency transformation of oat via microprojectile bombardment of seed-derived highly regenerative cultures. Plant Science 1 4 8, 9-17.

38. Gless, C., Lorz, H. and Jahne-Gartner, A. ( 1998) Establishment of a highly efficient regeneration

system from leaf base segments of oat (Avena sativa L. ). Plant Cell Reports 17, 441-445.

39. Kaeppler, H. F ., Menon, G. K ., Skadsen, R. W ., Nuutila, A. M. and Carlson, A. R. (2000) Transgenic oat plants via visual selection of cells expressing green fluorescent protein. Plant Cell Reports 19,661-666.

40. Somers, D. A. ( 1999) Genetic engineering of oat, in Molecular Improvement of Cereal Crops, (Vasil, I.and Phillipes, R ., eds. ) , Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

41. Choi, H. W ., Lemaux, P. G. and Cho, M. J.- (2001) High frequency of cytogenetic aberration in transgenic oat (Avena sativa L. ) plants. Plant Science 160, 761-762.

4 2. Zhang, S ., Cho, M. J . , Koprek, T ., Yun, R ., Bregitzer, P. and Lemaux, P. G. ( 1999) Genetic

transformation of commercial cultivars of oat (Avena sativa L ) and barley ( Hordeum vulgare L. ) using in

vitro shoot meristematic cultures derived from germinated seedlings. Plant Cell Reports 18, 959-966.

43. Zhong, H ., Srinivasan, C. and Sticklen, M. B. (1992) In vitro morphogenesis of corn (Zea mays L . ).II. Differentiation of ear and tassel clusters from cultured shoot apices and immature inflorescences. Planta 187, 483-4 89.

44. Zhong, H ., Wang, W. and Sticklen, M. B. ( 1998) In vitro morphogenesis of Sorghum bicolor ( L . )

Moench: efficient plant regeneration from shoot apices. Journal o f Plant Physiology 153, 719-726.

45. Devi, P ., Zhong, H. and Sticklen, M. B. (2000 ) In vitro morphogenesis of pearl millet ( Pennisetum glaucum ( L. ) R. Br. ) : efficient production of multiple shoots and inflorescences from shoot apices. Plant Cell Reports 19, 5 46-550.

4 6. Ahmad, A., Zhong, H ., Wang, W. and Stickler!, M. B. (2001) Shoot apical meristem : In vitro plant regeneration and morphogenesis in wheat ( Triticum aestivum L. ). In Vitro Cellular and Developmen. Biology-Plant 38, 163-167.

4 7. Maqbool, S. B ., Zhong, H ., El-Maghraby, Y ., Ahmad, A., Chai, B ., Wang, W ., Sabzikar, R.

;md Slicklrn, M. H. (2002) Comf^olence of onl (Avena saliva 1,. ) shool npir/il mfvrisl(v.ms on inlf'^rnlivr

Uanslomialion, inlicriLcd cxprcsbioii, and osmotic tolerance ol Lranygcnic linc.s conlaining {\iv, hva\ ^ TItroretical and Applied Genetics 105, 201-208.

4 8. Xu, D ., Duan, X., Wang, B ., Hong, B ., Ho, T. and Wu, R. ( 1996) Expression of a late embryo-

genesis abundant protein gene, HVAl, from barley confers tolerance to water deficit and salt stress in

transgenic rice. Plant Physiology 110, 2 49-257. 168 Maqbool et al.

49. Patnaik, D. and Khurana, P. (2003) Genetic transformation of Indian bread ( T. aestivum L. ) and pasta(T. durum L. ) wheat by particle bombardment of mature embryo-derived calli. BMC Plant Biology 3,1- 11.

50. Maqbool, S. B ., Zhong, H. and Stickler!, M. B. (200 4 ) Genetic engineering of oat (Avena sativa L . )via the biolistic bombardment of shoot apical meristems, in Transgenic Crops of the World-Essential Protocols, Chap. 5, (Curtis, I. S ., ed. ) , Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp. 63-78.

51. Oraby, H. F ., Ransom, C. B ., Kravchenko, A. N. and Sticklen, M. B. (2 0 0 5 ) Barley HVA1 gene confers salt tolerance in R3 transgenic oat. Crop Science 4 5, 2218-2227.

52. Murashige, T. and Skoog, F. ( 1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiology Plant 15, 473-4 97.

53. Strickberger, M. W. (1985) Genetics, 3rd ed. Macmillan, New York, pp. 126-146.

54. Southern, E. M. (1975) Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. Journal of Molecular Biology98, 503-517.

55. Sambrook, J . , Fritsch, E. F. and Maniatis, T. ( 1989) Molecular cloning : A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Lab, New York.

56. Bradford, M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Annals o f Biochemistry72, 24 8-254 .

57. JaKerson, R. A., Kavanagh, T. A. and Bevan, M. W. (1987) GUS fusions : P-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO Journal 6 , 3901-3907.

58. (J. R. C., Milach, S. C. K ., Pasquali, G. and Barro, R. S. (2002) Somatic embryogenesis and

phinl regeneration derived from mature embryos of oat. Pesquisa Agropecuaria Brasileira 37, 123-130.

燕麦(Avena sativa L. ) 是一种冷季型一年生禾谷类作物,其全球产量位于小麦、玉米、水稻、大麦、高粱和小米之后,为世界第七大禾谷类作物。不同于其他禾谷类作物,绝大多数的燕麦在国内流通消耗,只有少量出口贸易 [1,2 ] 。燕麦喜好较冷和潮湿的气候,能够在不同类型的土壤上生长 [3,4]。其生长相比小麦和大麦来说,能适应更大范围的土壤 pH,如 pH 从 5.5~7.0,有些燕麦品种甚至可以在 pH 4.5 的土壤上生长。另外,燕麦种植的土壤石灰施用量很低 [5],但是其生长和结实需要充足的水分。因此,俄罗斯、加拿大、美国、芬兰和波兰是主要的燕麦生产国 [6 ]。而燕麦最高的产量一般来自新西兰、瑞士、德国、英国、爱尔兰、瑞典和法国等国 [7]。

因为燕麦的蛋白质和必需矿物质含量高,几个世纪以来,一直是优良的家畜伺料[ 8 ]。另外,燕麦的高纤维含量能促进消化 [ 6 ]。燕麦也可用于食品加工,如燕麦片、燕麦淀粉和饼干。近来燕麦和燕麦麸作为健康食物也大受欢迎,因为其能够帮助减少血液中的胆固醇,并且能够调节胃肠功能 [6 ]。最近燕麦更是被用于化妆品生产,因为其含有两种活性成分—— 燕麦生物碱和葡聚糖。这两种物质有利于保护皮肤,用于抵抗刺激物和帮助晒伤的皮肤再生等。燕麦还可用于造纸和酿造工业,以及用来生产塑料、杀虫剂和防腐剂 [7]。燕麦还可作为伺料、牧草,用于生产绿肥,或作为作物覆盖物。作为作物覆盖物时,燕麦能够延长土壤使用寿命,抑制杂草生长,控制土壤的侵蚀和增加有机成分 [4,8]。以上原因直接导致了对优质燕麦需求的增加。

环境胁迫,如干旱和盐碱,限制了全球农业产量 [9,10]。尤其是盐碱,影响了全球约 1/3 的灌溉农业用地 [11, 12]。由于不合理的耕作,世界可耕地面积正在逐渐减少 [13]。这使得农民不得不在容易发生盐碱的地区种植和收获受盐胁迫的农作物[14] 。燕麦对高温和干旱的气候很敏感,其产量依赖于生长季节中供水量是否充足

[15] 。燕麦对盐胁迫的适应性还知之不多,但一般认为其对盐胁迫的耐受性要比其他的谷类或伺料作物低 [16]。有报道称盐害能够降低不同燕麦品种种子的萌发率和影响萌发后的生长 [16, 17]。倒伏是影响燕麦产量的另一个因素。同时,燕麦也易受大麦黄条矮缩病毒和有害昆虫的影响 [18,19]。人们已经对燕麦品种进行了改良,以提高其抗病性,但规模有限 [20]。

由于不同燕麦品种间基因组背景的保守性及低效的选育方法,人们难以通过传统育种手段来解决燕麦生产中的问题 [21]。但是,现代作物改良策略,如生物技术,可以与传统育种手段相结合来促进农业增产 [22~24]。生物技术作为一种具有良好前景的方法,不仅可解决发展中国家面临的有限的作物产量的问题,而且能促进可持续农业的发展 [25, 26 ]。因此,选择具有髙产遗传潜力的品种,或通过遗传工程手段培育抗性品种,有助于提高胁迫条件下燕麦的产量水平。

最近,禾谷类作物的改良得益于组织培养和优良性状基因的遗传工程改良 [27~29 ]。但是,关于不受基因型影响的燕麦体外再生和基因工程体系的研究报道仍然有限 [29~34]。1996 年,张等发展了一种不受基因型影响的高效的茎尖分生组织再生体系,可用于商业化燕麦品种的遗传转化 [35]。其后的研究报道了基因枪介导的转化体系,

应用成熟胚来源的愈伤 [36,37]、幼苗叶基部 [ 38 ] 和未成熟胚来源的胚性愈伤组织作为受体进行遗传转化 [39]。但是,胚源性愈伤不适于常规的燕麦转化,因为延长组织培养时间可能造成体细胞无性系的变异 [40,41]。因此,来自成熟种子的多芽分生组织,可作为另一种不受基因型影响的具有再生能力的受体组织,用于商业化燕麦品种的遗传转化 [35~47]。采用这一体系,可以高效地进行组织再生且重复性好,获得的转基因植株具有很高的结实率和基因组稳定性。

这里,我们介绍了茎尖分生组织结合基因枪介导,对三个燕麦品种进行遗传转化的方法,以及利用该方法转化抗渗透胁迫基因 hva1,提高燕麦对渗透胁迫的耐受性。此外 ,我们还介绍了对转基因燕麦的分子和生化分析,以证实转基因的整合,表达稳定并可遗传,同时检测了 hva1 基因在转基因植株中的表达及其对盐碱和缺水的耐受性的影响。

2. 材料

2.1 燕麦品种

(1) Ogle ( Brave/2/Tyler/Egdoion23 )

(2) Pacer (CoachmanxCI 1382)

(3) Prairie(IL73-5743xOgle)

2.2 质粒

(1) pBY520 包含两个基因:一个是来源于 Streptomyces hygroscopicus 的抗除草剂基因 —— 草胺膦乙酰基转移酶基因(bar),作为选择标记,该基因由花椰菜病毒启动子(CaMV35S ) 驱动,以农杆菌胭脂氨酸合成酶基因(nos ) 的 3' 非编码区为终止子。胁迫抗性基因来源于大麦胚胎发生后期的富集蛋白基因(Shva1) ,由水稻肌动蛋白 Act1 的启动子驱动,以马铃薯蛋白水解酶抑制子II ( pin ll ) 的 3' 非编码区为终止子( 图 10.1) 。

(2) pAct1-D:含有由 Act1 启动子驱动并利用 nos 终止子的大肠杆菌 β-葡萄糖醛酸酶基因(gus) ( 图 10.1 )。

2 . 3 培养基

( 1 ) MS1 ( 萌发培养基):4.3 g/L MS [ 52 ] 基本培养基和维生素(GIBC0 BRL Rockville,Maryland ) ,30 g/L蔗糖( Sigma,St. Louis,MO, USA ) ,3 g/L phytagel (Sigma), pH 5.6。

( 2 ) MS2 ( 芽增殖培养基):MS 培养基,30 g/L 蔗糖,500 mg/L 酪蛋白酶水解物 (Sigma) , 0.5 mg/L 2,4-D (Sigma) , 2 mg/L N6- 芐基腺嘌呤(Sigma ) , 3 g/L phytagel,pH 5. 6。

( 3 ) MS3 ( 粒子轰击培养基):MS 培养基,30 g/L 蔗糖,500 mg/酪蛋白酶水解物(Sigma) ,0~5 mg/L 2,4-D ( Sigma) ,2 mg/L N6-芐基腺嘌呤(Sigma) ,5 g/L phytagel。

( 4 ) MS4(低选择压的芽增殖培养基):MS2 培养基,5 mg/L 草胺膦(Sigma) 或 2 mg/L 双丙氨膦(Meiji Seika Kaisha, Japan) 。

( 5 ) MS5(高选择压的芽增殖培养基): MS2 培养基,10 mg/L 草胺膦或 3 mg/L 双丙氨膦。

( 6 ) MS6(芽再生培养基):MS 培养基,20 g/L 蔗糖,0.5 mg/L N6-苄基腺嘌呤,0.5 mg/L B 吲哚三丁酸(Sigma) ,15 mg/L 草胺膦或 5 mg/L 双丙氨膦,3~5 g/L phytagel,pH 5.6。

( 7 ) MS7(生根培养基):2.15 g/L MS 培养基,10 g/L 蔗糖,15 mg/L 草胺膦或 5 mg/L 双丙氨膦,3~5 g/L phytagel,pH 5.8。

( 8 ) MS8(盐胁迫培养基):2.15 g/L MS 培养基,10 g/L 蔗糖,100 mmol/L NaCl (Sigma),3~5 g/L phytagel, pH 5.8。

( 9 ) MS9(渗透胁迫培养基):2.15 g/L MS 培养基,10 g/L 蔗糖,200 mmol/L manifold (Sigma) ,3~5 g/L phytagel, pH 5.8。

所有的培养基需 121℃ 高压蒸汽灭菌 20 min。激素、除草剂和抗生素在培养基灭菌后添加(40~50°C ) 。

2.4 其他材料

( 1 ) Clorox 漂白剂 (Clorox Professional Products Company, Oak- land, CA 94612)

( 2 ) 塑料植物盆(8 cm 方格,Griffin Green House and Nursery Supplies,1619 Main Street, Tewksbury, MA 01876)。泥炭和珍珠岩混合土 (Griffin Green House and Nursery Supplies)。

( 3 ) 混合土( Metro Mix 360 Soil; Griffin Green House and Nursery Supplies)

( 4 ) Ignite 含有 200 g/L ( 16. 222% ) 活性成分草胺膦的除草剂(1% Ignite Hoechst-Roussel Agri-Vet Company, NJ)

( 5 ) 蛋白提取缓冲液:50 mmol/L 磷酸钠缓冲液(pH 7.0 ) ,10 mmol/L EDTA(乙二胺四乙酸), 0.1% (V/V) Triton X-100,0.1% (m/V ) Sarkosyl,10 mmol/L 疏基乙醇,10 mmol/L PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride)。

( 6 ) 碱性磷酸酶缓冲液:100 mmol/L Tris-base,100 mmol/L NaCl,5 mmol/L MgCl2( pH 9.8 ) 含有 0.33 mg/ml NBT (Nitro blue tetrazolium ) ,0.16 mg/ml BCIP (5 - bromo - 4 -chloro-3 -indolyl phosphate)。

( 7 ) GUS底物:10 mmol/L EDTA ( pH 7.0 ) ,0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.0 ) ,1~5 mmol/L X-Gluc(X- Gluc 可以用二甲基亚砜溶解,Sigma)。

3. 注释

注 1 : 种子还可用 70% 乙醇消毒 2 min;用无菌蒸馏水洗一次,然后在 50% Clorox 漂白剂中浸泡 15 min,期间以 0.5 g 持续振荡。

注 2 : 用灭菌的滤纸汲取种子上的水分(3 mm;VWR) ,再将消毒后的种子放置于 MS1 培养基上。

注 3 : 芽尖包含有顶端分生组织、2~3 个叶原基和叶基。芽尖是靠近叶基的膨大部分。

注 4 : 每一品种放置 7~8 个皿。为获得不同品种的最佳效果,用不同浓度的 2 ,4 -D ( 0 mg/L 和 0.5 mg/L ) 和 N6-苄基腺嘌呤(0 mg/L、0.5 mg/L、1.0 mg/L 、2.0 mg/L、4.0 mg/L 和 8.0 mg/L ) 的组合。

注 5 : 计算丛生芽的相对分化频率(见 [47])。

注 6 : 为获得多个质粒转化的最佳结果,用不同质粒摩尔比,如 3 : 1 或 2 : 1 (两个质粒)、1 : 1 : 1 或 3 : 2 : 1 (三个质粒),带有选择标记的质粒是比值中的最后一个(即浓度最低)。

注 7 : 用由芽分生组织分化而来的、培养 1 个月的丛生芽培养物进行基因枪轰击转化 [ 图 10. 2 (a ) ] ; 如有必要,在轰击之前去除胚芽鞘和叶片使丛生芽外露。

注 8: 在 26 mmHg 气压下,用基因枪微粒加速装置(PDS 1000/He, Bio- Rad) 进行轰击,可裂膜到载体膜的距离为 1. 5 cm, 载体膜到终止屏的距离为 2 cm, 终止屏到样品的距离为 6. 5 cm, 氦气压为 1550 psi。

注 9 : 第一次轰击后,将组织放在 25℃ 暗培养直到第二次轰击。

注 10 : 在温室中生长 1 个月后,将植株移到大盆中(12 cm2) ,促进其生长; 如有必要,每周施用一次 Peters 20 : 20 : 20 的 肥 料(Griffin Green House and Nursery supplies)。

注 11 : 除草剂的使用:在三叶期最幼嫩的叶片上涂抹除草剂,到六叶期时对整个植株喷洒 1% Ignite 除草剂,草胺磷活性成分为 200 g/L( 16. 222% ) 。

注 12 : 用不同的转基因独立株系种子(R。、R1 或 R2)。在本实验中使用来自 5 个独立的转基因株系的 R2 代 Ogle BRA-82、 Ogle BRA-17、 Ogle BRA-8、 Ogle BRA-19 和 Ogle BRA-41。

注 13:将代转基因种子种植于 MS7 选择培养基上,以筛选转基因和非转基因的植株。选用在选择培养基上能够生长的苗,测试对胁迫的抗性。

注 14 : 植物鲜重:从 Magenta 盒中将整株植株小心取出,不要损伤生长于培养基中的根系,将根系上的培养基清洗掉,再用纸巾汲干,用天平称重(Precision Weighing Balances, Bradford, MA 01835)。

注 15 : 植物干重:将整株植株放入已称重的 3 mm 滤纸上,滤纸已经烘干至恒重。用铝箔包裹,置于 110℃ 恒 温箱中(VWR) 烘干 24 h。将样品从恒温箱取出放入干燥器中(VWR) ,避免称重前样品吸水。待其降至室温,称重后减去滤纸的质量,得出每一植株的质量。

注 16 : 在培养基中加入甘露醇,使离体条件下生长的植株产生缺水或渗透胁迫。

注 17 : 这是一个优化的方法,以评估表达 Ami 的转基因株系在温室中环境下对缺水胁迫的耐受性 [48]。

注 18: 5 个燕麦 Ogle 独立转基因株系 R3 代 BRA -8、 BRA-17、 BRA-19、 BRA- 41 和 BRA-82,由本研究中的 R2 代植株繁殖获得 [47],并与对照植株一起置于温室中生长。

注 19 : 每一盐溶液处理一组植株。每天浇灌一次,确保渗透完全,并防止盐过量。

注 20 : 还可进行其他性状的测定,如分蘖数、至抽穗的天数、剑叶叶面积、千粒重 、每穗结实率、花序长度、每个花序的小花数等 [48, 51] 。

4. 参考文献

1. Hitchcock, A. S. ( 1971) Manual of the grasses of the United States. Originally published in 1950 as U. S.D. A. Miscellaneous publication No. 200. Dover, New York. Second edition revised by Chase, A.

2. Munz, P. A. and Keck, D. D. (1973) A California Flora (with Supplement by P. Munz). University of

California Press, Berkeley, California.

3. Madson, B. A. (1 9 5 1 ) Winter Covercrops. Circular 17 4 , California Agricultural Extension Service,

College of Agriculture, University of California, June 1951.

4. Johnny 』 s selected seeds ( 1983) Green Manures-A Mini Manual. Johnny, s selected seeds, Albion,Maine 04910.

5. Verhallen, A . ,Hayes, A. and Taylor, T. (2003) Cover crops-Oats, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and

Rural Affairs, Ontario, Canada.

6. Gibson, L. and Benson, G. (2002) Origin, history, and uses of oat ( Avena sativa ) and wheat ( Triticum aestivum). Course Agronomy 212, Iowa State University, Department of Agronomy, Iowa.

7. http : //interactive, usask. ca/Ski/agriculture/crops/cereals/oats. html. Agriculture crops cereals oats.

Saskatchewan Interactive, last updated 14 Dec 2002.

8. Forsberg, R. A. and Shands, H. L. ( 1989) Oat breeding in Plant Breeding Reviews. Vol. 6 , (Janick, J . ,ed. ) , Timber Press, Portland, OR, pp 167-207.

9. Boyer, J. S. (1982) Plant productivity and environment. Science 218, 444-448.

10. Roy, M. and Wu, R. (2 0 0 2 ) Overexpression of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase gene in rice

increases polyamine level and enhances sodium chloride-stress tolerance. Plant Science 163, 987-992.

11. Apse, M. P . , Aharon, G. S ., Snedden, W. A. and Blumwald, E. (1999) Salt tolerance conferred by over expression of a vacuolar Na+/ H + antiport in Arabidopsis. Science 285, 1256-1258.

12. Schachtman, D. and Lui, W. ( 1999) Molecular pieces to the puzzle of the inLeraclion l)elween |) 〇 lassiurn and sodium uptake in plants. Trends in Plant Science 4 , 281-287.

13. Qadir, M ., Qureshi, H. H. and Ahmad, N. ( 1998) Horizonlal flushing : a promising ameliorative technology for hard salinesodic and sodic soils. Soil Tillage Research 4 5, 119-131.

14. Cherry, J. H ., Locy, R. D. and Rychter, A. (1999) Proc. NATO Adv. Res. Workshop, Mragowa, Poland. 13-19 June. Kluwer, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

15. Martin, R. J . , Jamieson, P. D ., Gillespie, R. N. and Maley, S. (2001) Effect of timing and intensity of drought on the yield of oats {Avena sativa L. ) . Proceeding of the 10th Australian Agronomy Conference,Hobart.

16. Murty, A. S ., Misra, P. N. and Haider, M. M. ( 198 4 ) Effect of different salt concentrations on seed germination and seedling development in few oat cultivars. Indian Journal o f Agricultural Research 18,129-132.

17. Verma, 0. P. S. and Yadava, R. B. R. (1986) Salt tolerance of some oats {Avena sativa L. ) varieties at germination and seedling stage. Journal o f Agronomy and Crop Science 156, 123-127.

18. Schonbeck, M. W. (1988) Cover Cropping and Green Manuring on Small Farms in New England and New York: An Informal Survey. Research Report 10, New Alchemy Institute, East Falmouth, MA 02536.

19. Koev, G ., Mohan, B. R ., Dinesh-Kumar, S. P ., Torbert, K. A., Somers, D. A. and Miller, W. A.

(1998) Extreme reduction of disease in oats transformed with the 5 5 half of the barley yellow dwarf virus PAV genome. Phytopathology 88, 1013-1019.

20. Stoskopf, N. C. (1985 ) Barley and Oat, in Cereal Grain Crops, (Stoskopf, N. C ., ed. ) , Reston Publishing , Reston, Virginia, pp. 444 -4 58.

21. Cushman, J. C. and Bohnert, H. J. (2000) Genomic approach to plant stress tolerance. Current Opinions in Plant Biology 3, 117-12 4.

22. Abebe, T ., Guenzi, A. C., Martin, B. and Cushman, J. C. ( 2003 ) Tolerance of mannitol-

accumulating transgenic wheat to water stress and salinity. Plant Physiology 131, 17 48-1755.

23. Epstein, E ., Norlyn, J . , Rush, D ., Kings-bury, R ., Kelley, D ., Cunningham, G. and Wrona, A.

(1980) Saline culture of crops : a genetic approach. Science 210, 399- 4 0 4 .

24. Ribaut, J. M. and Hoisington, D. A. (1998) Marker assisted selection : new tools and strategies. Trends in Plant Science 3, 236-239.

25. FAO. (1 9 9 9 ). Biotechnology in food and agriculture, http : //www. fao. org/unfao/ bodies/COAG/CO-AG15/X0074 E. htm.

26. Sharma, H. C ., Crouch, J. H ., Sharma, K. K ., Seetharama, N. and Hash, C. T. (2002) Application of biotechnology for crop Transformation of Oats and Its Application 167 improvement: prospects and constraints. Plant Science 163, 381-395.

27. Mazur, B ., Krebbers, E. and Tingey, S. ( 1999) Gene discovery and product development for grain quality traits. Science 285, 372-375.

28. Rines, H. W ., Phillips, R. L. and Somers, D. A. (1992) Application of tissue culture to oat improvement, in Oat Science and Technology, ( Marshall, H. G ., and Sorrels, M. E ., eds. ) , American Society of Agronomy and Crop Science Society, Madison WI, pp. 777-791.

29. Somers, D. A., Torbert, K. A., Pawlowski, W. P. and Rines, H. W. ( 199 4 ) Genetic engineering of oat, in Improvement of Cereal Quality by Genetic Engineering , (H en ry ,R. J. and Ronalds, J. A . ,ed s.), Plenum, New York, pp. 37-46.

30. Cummings, D. P . , Green, C. E. and Stuthman, D. D. ( 1976) Callus induction and plant regeneration in oats. Crop Science 16, 465-4 70.

31. Rines, H. W. and McCoy, T. J. ( 1981) Tissue culture initiation and plant regeneration in hexaploid species of oats. Crop Science 21, 837-8 42.

32. Bregitzer, P ., Bushnell, W. R ., Somers, D. A. andRines, H. W. (1989) Development and characterization of friable, embryogenic oat callus. Crop Science 29, 798-803.

33. Rines, H. W. and Luke, H. H. (1985) Selection and regeneration of toxin insensitive plants from tissue cultures of oat (Avena sativa) susceptible to Helminthosporium victoriae. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 7 1 , 16-21.

34. Somers, D. A., Rines, H. W ., Gu, W ., Kaeppler, H. F. and Bush-Nell, W. R. ( 1992) Fertile

transgenic oat plants. Bio/Technology 10, 1589-159 4.

35. Zhang, S. ^ Zhong, H. and Stickler!, M. B. (1996) Production of multiple shoots from apical meristems of oat (Avena sativa L. ). Journal o f Plant Physiology 1 4 8, 667-671.

36. Torbert, K. A ., Rines, H. W. and Somers, D. A. (1998) Transformation of oat using mature embryo-drived tissue cultures. Crop Science 38, 226-231.

37. Cho, M. J . , Jiang, W. and Lemaux, P. G. ( 1999) High frequency transformation of oat via microprojectile bombardment of seed-derived highly regenerative cultures. Plant Science 1 4 8, 9-17.

38. Gless, C., Lorz, H. and Jahne-Gartner, A. ( 1998) Establishment of a highly efficient regeneration

system from leaf base segments of oat (Avena sativa L. ). Plant Cell Reports 17, 441-445.

39. Kaeppler, H. F ., Menon, G. K ., Skadsen, R. W ., Nuutila, A. M. and Carlson, A. R. (2000) Transgenic oat plants via visual selection of cells expressing green fluorescent protein. Plant Cell Reports 19,661-666.

40. Somers, D. A. ( 1999) Genetic engineering of oat, in Molecular Improvement of Cereal Crops, (Vasil, I.and Phillipes, R ., eds. ) , Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

41. Choi, H. W ., Lemaux, P. G. and Cho, M. J.- (2001) High frequency of cytogenetic aberration in transgenic oat (Avena sativa L. ) plants. Plant Science 160, 761-762.

4 2. Zhang, S ., Cho, M. J . , Koprek, T ., Yun, R ., Bregitzer, P. and Lemaux, P. G. ( 1999) Genetic

transformation of commercial cultivars of oat (Avena sativa L ) and barley ( Hordeum vulgare L. ) using in

vitro shoot meristematic cultures derived from germinated seedlings. Plant Cell Reports 18, 959-966.

43. Zhong, H ., Srinivasan, C. and Sticklen, M. B. (1992) In vitro morphogenesis of corn (Zea mays L . ).II. Differentiation of ear and tassel clusters from cultured shoot apices and immature inflorescences. Planta 187, 483-4 89.

44. Zhong, H ., Wang, W. and Sticklen, M. B. ( 1998) In vitro morphogenesis of Sorghum bicolor ( L . )

Moench: efficient plant regeneration from shoot apices. Journal o f Plant Physiology 153, 719-726.

45. Devi, P ., Zhong, H. and Sticklen, M. B. (2000 ) In vitro morphogenesis of pearl millet ( Pennisetum glaucum ( L. ) R. Br. ) : efficient production of multiple shoots and inflorescences from shoot apices. Plant Cell Reports 19, 5 46-550.

4 6. Ahmad, A., Zhong, H ., Wang, W. and Stickler!, M. B. (2001) Shoot apical meristem : In vitro plant regeneration and morphogenesis in wheat ( Triticum aestivum L. ). In Vitro Cellular and Developmen. Biology-Plant 38, 163-167.

4 7. Maqbool, S. B ., Zhong, H ., El-Maghraby, Y ., Ahmad, A., Chai, B ., Wang, W ., Sabzikar, R.

;md Slicklrn, M. H. (2002) Comf^olence of onl (Avena saliva 1,. ) shool npir/il mfvrisl(v.ms on inlf'^rnlivr

Uanslomialion, inlicriLcd cxprcsbioii, and osmotic tolerance ol Lranygcnic linc.s conlaining {\iv, hva\ ^ TItroretical and Applied Genetics 105, 201-208.

4 8. Xu, D ., Duan, X., Wang, B ., Hong, B ., Ho, T. and Wu, R. ( 1996) Expression of a late embryo-

genesis abundant protein gene, HVAl, from barley confers tolerance to water deficit and salt stress in

transgenic rice. Plant Physiology 110, 2 49-257. 168 Maqbool et al.

49. Patnaik, D. and Khurana, P. (2003) Genetic transformation of Indian bread ( T. aestivum L. ) and pasta(T. durum L. ) wheat by particle bombardment of mature embryo-derived calli. BMC Plant Biology 3,1- 11.

50. Maqbool, S. B ., Zhong, H. and Stickler!, M. B. (200 4 ) Genetic engineering of oat (Avena sativa L . )via the biolistic bombardment of shoot apical meristems, in Transgenic Crops of the World-Essential Protocols, Chap. 5, (Curtis, I. S ., ed. ) , Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp. 63-78.

51. Oraby, H. F ., Ransom, C. B ., Kravchenko, A. N. and Sticklen, M. B. (2 0 0 5 ) Barley HVA1 gene confers salt tolerance in R3 transgenic oat. Crop Science 4 5, 2218-2227.

52. Murashige, T. and Skoog, F. ( 1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiology Plant 15, 473-4 97.

53. Strickberger, M. W. (1985) Genetics, 3rd ed. Macmillan, New York, pp. 126-146.

54. Southern, E. M. (1975) Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. Journal of Molecular Biology98, 503-517.

55. Sambrook, J . , Fritsch, E. F. and Maniatis, T. ( 1989) Molecular cloning : A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Lab, New York.

56. Bradford, M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Annals o f Biochemistry72, 24 8-254 .

57. JaKerson, R. A., Kavanagh, T. A. and Bevan, M. W. (1987) GUS fusions : P-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO Journal 6 , 3901-3907.

58. (J. R. C., Milach, S. C. K ., Pasquali, G. and Barro, R. S. (2002) Somatic embryogenesis and

phinl regeneration derived from mature embryos of oat. Pesquisa Agropecuaria Brasileira 37, 123-130.